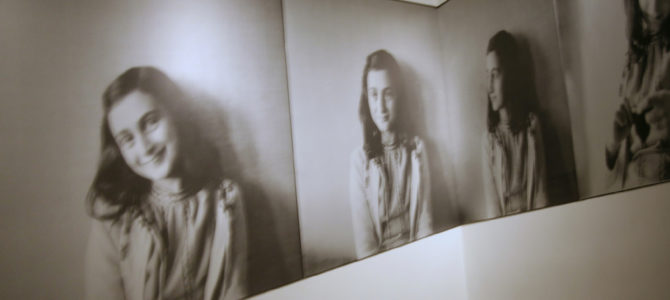

When Confederate statues were first being removed around the country and other monuments were being questioned in the wake of the Charlottesville street fighting, my family got to tour a historic site across the Atlantic. More than a million visitors walk through the Anne Frank House every year in Amsterdam to see the secret annex where eight people—including Otto and Edith Frank and their two daughters, Margot and Annelies—hid for two years to escape the persecution and systematic removal of Jews from occupied Amsterdam.

If anyone had the right to keep the painful history of his family private, it was Otto Frank. The Nazis eventually found the Franks’ hiding place, and Otto was the only Holocaust survivor of the eight people hidden in the annex in his office building. After the war ended, Frank returned to the annex, found and published his daughter’s diary, and worked to help establish the Anne Frank House as a museum documenting their lives and the genocide that occurred during World War II.

Visiting the Scene of the Crime Does Change You

Despite having studied WWII and the Holocaust extensively, nothing prepared me for the emotions I felt while walking around in the rooms where eight people desperately hid in hopes of survival. When my family of six was behind the bookcase that once hid the entrance to the secret annex, I couldn’t help but feel transported in time to Amsterdam under Nazi occupation.

The deeper we got into the rooms, the more my body tightened as fear and despair overcame me. As my toddler made noises and the floor creaked beneath my feet, I had to remind myself that I did not have cause for panic. From conversations with other visitors, I got the impression that many experience fear and grief during their tour.

The reality of life for those persecuted under Nazi occupation is horrifying. I don’t have to visit the Anne Frank House to know that. But when the opportunity presents itself to visit a living historical site, the effect on one’s spirit can be more significant than any book or lecture.

Surely Otto Frank knew that opening the Anne Frank House for the public to tour would evoke painful memories for those whose lives the horror of the Holocaust directly affected. Otto Frank also knew that the Anne Frank House had the potential to teach the truth of the evil ideology that caused his family so much loss. His vision for the Anne Frank House was to be “a place serving as a warning from the past, but focused on the future.” Otto Frank knew the power of history.

Showing History Isn’t the Same as Celebrating It

History shows us the best and worst of humanity. When history is forgotten, we all lose the opportunity to learn and grow from our ancestors, however flawed or noble they may have been. For the sake of our own memories and especially for future generations, we have to be careful that we don’t erase history, even the most offensive history, from our towns.

In America, cities are carefully considering what to do about potentially divisive statues and monuments. From New York City Mayor Bill De Blasio’s 90-day review of all public monuments to find symbols that represent hate to the discussion of the merit of Christopher Columbus statues in Columbus, Ohio, San Jose, California, and Buffalo, New York, officials are taking complaints about monuments seriously.

A short 10-mile drive from my childhood home, a monument marking a former slave auction site is the subject of an online petition that currently has more than 2,500 signatures requesting its removal. Located about an hour south of Washington D.C. and 90 minutes northeast of Charlottesville, Fredericksburg is the childhood home of George Washington, the site of a Civil War battle, and the location of an exodus in 1862 of 10,000 slaves crossing to freedom, amongst other historic events.

This small plaque and stump-shaped stone block marks the spot where at least 12 slaves were sold in Fredericksburg, but it is not celebrating the abhorrent treatment of people as good; the block serves to chronicle history. Fredericksburg mayor Mary Katherine Greenlaw said, “In this discussion, we are talking about what is the history. We are not talking about a memorial or something that is after the fact or a glorification. This is the history. That is the spot. This is the significant distinction.”

As a Fredericksburg-area native, I would prefer that my hometown didn’t have such a wicked past, but since it does, residents and visitors alike can learn from the auction block’s presence in the middle of the city. The fact that humans were sold there is not something I want to forget; it places a burden of responsibility on me to remember and to tell my children the sins of the city and our country. Walking through Fredericksburg and coming upon the block is a reminder to repent from any hate that breeds inside one’s soul and to look for ways to heal.

Denial Does Not Erase the Reality We All Need to Deal With

Another Fredericksburg native, David Caprara, made a strong distinction between the Confederate statues under fire and the auction block: “The slave block is not a manmade creation to honor history; it is history. There is no question over the interpretation of the block – it is a living symbol of hate, oppression, and the agony of black families that were physically, mentally, and spiritually brutalized by their white hypocrite oppressors for generations.”

The is no doubt that sites like the Anne Frank House and the slave auction block can and should evoke strong feelings of sorrow, but sterilizing our towns and cities of statues and monuments that evoke strong feelings may cause us to be frail people who can’t cope with our history. What happens if we remove every public evidence of complicated history that exists in our country? We may feel relief for a time, but our children will not be given spontaneous opportunities to learn from the sins of our past when walking through our cities. Future generations will not see how complex their hometowns’ histories are and will miss sobering chances to be warned about committing the same grievous sins.

Some monuments provide an account of a wicked past, giving us the responsibility to future generations to tell them of these deeds that haunt our past. Reading a textbook is only so helpful, but having a visual in a city allows people to remember that actual history, even the ugliest of history, took place right where they live, not just in some faraway land and time of history books.

This is why Otto Frank spent his money to preserve the Anne Frank House for people to visit. It is also why we need to tread carefully before removing any historical site that has the potential to offend and instruct.