Gen. John Kelly has been brought to the West Wing with a mission so often given to military officers amid chaos: restore order and discipline. Kelly is a man of sterling reputation and achievement, and his appointment has produced a rush of optimism throughout the country and especially among Republicans. This is a problem.

It’s not that Kelly is a bad pick. Indeed, he might be one of the few people with enough bearing and courage still willing to serve in this administration who can face down some of the worst influences vying for the president’s attention. He may be among the very few people who can tell the president that his daughter and son-in-law are not the peers of confirmed members of the Cabinet.

Rather, the problem is that the public’s eagerness to see a general impose order on the White House—with the president’s blessing, no less—represents a potentially dangerous bargain that at least some Americans seem willing to forge with serving and retired members of the U.S. military: we will accept dysfunction in the Oval Office, it seems, so long as there are enough generals ensconced around it as insurance against disaster.

This is a complete reversal of long-lasting and stable traditions of American civil-military relations. The United States has a civilian commander in chief in order to provide a civilian check on the power of the military, not the other way around. To hope that Kelly and H.R. McMaster in the White House, and Gen. James Mattis at the Pentagon, will somehow restrain the president’s erratic impulses is a terrible development in our history, not because these are not fine men, but because too much reliance on them corrodes a key principle of the American constitutional order.

Yes, Americans Dig the Military

In fairness, President Trump’s fascination with the military is not new. After all, Richard Nixon brought in Gen. Alexander Haig to run the West Wing when his White House was sinking into the muck of Watergate in 1973. (This may not be a historical analogy Republicans want to recall.) Other presidents, too, have relied on military men in key positions in the White House and Cabinet, including Brent Scowcroft, Colin Powell, David Petraeus, James Jones, Eric Shinseki, James Clapper, Michael Hayden, and others. Some of these appointments were failures—Jones, Powell, and Petraeus ran into trouble as senior civilian officials, for example—and others, like Scowcroft, performed brilliantly.

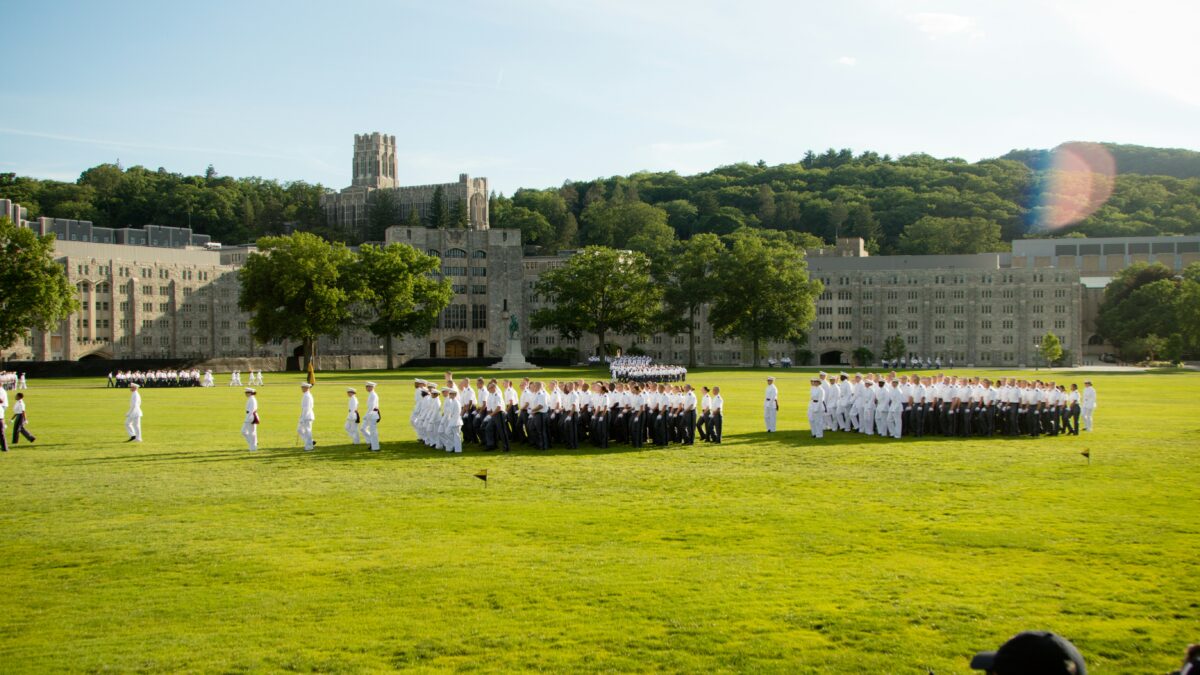

But the number of Trump’s military appointments in such proximity to the chain of command all at the same time, is remarkable, and all the more against the backdrop of the president’s plummeting approval ratings. As of this moment, the national security advisor, the secretary of Defense, the chief of staff—and, more distantly, the head of the U.S. prison system—are now all retired or serving generals, with a total of 13 stars among them. Rarely have so many served at once, and with so much political weight upon their shoulders.

Whatever the virtue of these officers, such appointments are also an obvious way to enhance credibility with an American public that has lost faith in almost all institutions except the military. This kind of gambit isn’t new, either: Ross Perot tried the same thing by dragooning Admiral James Stockdale as a running mate in 1992. It backfired in a wince-inducing debate moment, and hurt the reputation of Stockdale—a true American hero who was held prisoner in Vietnam—in the bargain.

Still, bringing military stars into the picture can buy some legitimacy, at least in the short term. As Jonathan Stevenson, an Obama NSC appointee, admitted in The New York Times:

At the beginning of the administration, most Democrats (myself included), and even a few Republicans, publicly hoped that a cadre of generals and former generals — Mr. Mattis, John Kelly at Homeland Security, Lt. Gen. H. R. McMaster at the National Security Council (who replaced retired Gen. Michael Flynn, a Trump loyalist) — would check Mr. Trump’s worse instincts.

Relying on the generals was always a dubious, ad hoc plan prompted by Mr. Trump’s uniquely troubling peculiarities. Generals aren’t supposed to make policy, let alone get involved in politics.

Notice that even as he decries the practice, Stevenson confesses that he, too, was placing his hopes in the generals.

Why We Separate Military and Civilian Rule

Nonetheless, trying to shore up our worries about the president by surrounding him with generals is dangerous idea. In almost every developed society, military officers think of themselves as more honorable and upright than the civilians around them, and to lean on the generals when the White House is off the rails encourages the notion that the officer corps is the only real reservoir of virtue and competence in the nation. It’s a deeply unhealthy and wrong-headed notion, especially in a constitutional republic.

Retirement is a fig leaf that does not solve this problem. Generals are still generals even when they retire: it’s why we address them by their rank even when they leave their command. (John F. Kennedy, in talking with his predecessor Dwight Eisenhower, referred to him as “general,” and Ike called the much younger JFK “Mr. President.”) Mattis had to get a waiver to serve as secretary of Defense specifically because the legislature, wisely, decided to put at least seven years of distance between wearing a uniform and assuming the top civilian defense post, and only to allow exceptions at the sufferance of the entire Congress.

The American tradition has until recently been a model to other nations. It is based on the idea that the experts in politics and the experts in violence maintain autonomy in completely separate domains, even though for the sake of coherent policy they must overlap on occasion. The generals and admirals do not decide national priorities; in return, the civilians do not micro-manage the military or its daily operations. The voters, for their part, are expected to choose civilians, not military officers, to exercise political judgment.

Both civilians and military officers have violated this pact on occasion, but America remains one of the very few nations where a coup remains unthinkable and military influence in policymaking is circumscribed by a civilian commander in chief and a separate legislature. Other countries have not been so fortunate; coups were rampant throughout the developing world for most of the mid-twentieth century, and even U.S. allies including France, Greece, and Turkey have had tragic failures of civil-military relations within the past six decades.

We Don’t Want to Get Used to This

The influx of generals so close to the Oval Office undermines this tradition. As Eliot Cohen—a dedicated Trump critic, but also a reserve officer and a Republican who served in the George W. Bush administration, wrote in The Atlantic about the Kelly appointment:

It contributes to the continuing decay of American civil-military relations. Those of us who were relieved to see James Mattis as secretary of defense, H. R. McMaster as national-security adviser, and Kelly himself as secretary of Homeland Security, felt that way partly out of appreciation for the virtues of all three men, but also, very largely, out of relief that their sanity might contain their boss’s craziness.

But it is inappropriate to have so many generals in policy-making positions; it is profoundly wrong to have a president regard the military as a constituency, and it is corrupting to have the Republican Party, such as it is, act as though generals have if not a monopoly then at least dominant market share in the qualities of executive ability and patriotism. It is unwise to have higher-level positions in the hands of officials who have openly expressed disdain for Congress—now a dangerously weak branch of government.

This last point about Congress is especially important. The reliance on martial virtue in the face of presidential chaos is dangerous not because it raises the threat of a coup, but because it creates an invitation to a kind of soft praetorianism, if only by sheer default. If Congress becomes acclimated to the idea that the military, instead of the legislative branch, should be watching over the president, why shouldn’t the American people and even the military itself come to the same conclusion?

If that seems an overstatement, consider that the Associated Press reported at the end of July that Mattis and Kelly agreed shortly after taking their respective offices at DoD and DHS to not be out of the country at the same time as members of Trump’s Cabinet. While this may fill many of us with relief, consider what it means: two of the top national security appointees in the Cabinet, both four-star Marines, agreed that the president could not be left without the oversight of at least one of them.

Kelly, McMaster, and Mattis are American heroes. One day, however, if the practice of calling in the generals and admirals when the executive branch loses its way continues and grows stronger, their posts near the center of presidential power might be occupied by far less virtuous officers. (It’s already happened, actually; consider that Lt. Gen. Michael Flynn was Trump’s first pick to be national security adviser, despite the squalid spectacle of Flynn, as a recently-retired three-star general, leading cheers at a political convention to toss a U.S. presidential candidate in prison.)

As in the case with everything in the Age of Trump, the danger is that this is yet another hazardous practice we’ll accept it because we will have simply gotten used to it. This is a risk not because Kelly, McMaster, and Mattis are bad generals, but because we are now forced to trust, far too much, that they are in fact very good generals, in every possible way.

During the 2016 campaign, one senior American general cautioned his colleagues against getting mired in what he called “the cesspool of domestic politics.” This general warned that the most dangerous thing would be for any president “to ever think for a second that he’s getting anything but the absolute best military advice, completely devoid of politics.” Good advice. That general’s name?

John Kelly.