The so-called “skinny repeal” amendment to the Senate health care reform bill died a lonely death last night after an hour of reporters interpreting body language on the Senate floor, with John McCain casting a decisive vote against the measure, thereby flipping the baying internet calls for his early demise after his motion to proceed vote on Tuesday to the other side of the partisan aisle.

His statement on why he voted against the bill is here. Skinny repeal was a rushed piece of legislation that would not have achieved lower premiums and would not represent true repeal and replacement of Obamacare – as Phil Klein wrote yesterday, it wasn’t just a bad bill, it was an insult.

The idea is that this bill is supposed to be the vehicle for senators to hash out a better bill in a conference with the House. But it’s totally bonkers for senators to vote in favor of a bill that they don’t want to become law, in the hopes that adding an additional legislative body to the negotiations will achieve what Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell could not in the past several months: get 50 senators to agree on a plan to repeal and replace Obamacare.

The political reality of the moment seemed to be lost on many observers: namely, that for all the last-minute lobbying of McCain in public view, there was very little similar lobbying of Lisa Murkowski, a Senator whose state has been particularly drubbed by the health care regime, but remained a solid no. Why would a rifle-shot bill that was utterly hands off on Medicaid, and just amounts to a lot of handwaving, still leave Murkowski in the “No” category? The political actions of the White House in the past week tell the tale.

James Hohmann has the right idea.

A lot of the media coverage in the wake of the vote will focus on McCain, and Collins was always going to vote ‘no.’ But Murkowski’s opposition was equally decisive and perhaps most illustrative of the problems ahead for Trump. Trump, who won Alaska by 15 points, ripped the state’s senior senator on Twitter Wednesday after she opposed a key procedural motion to open debate on health care…

Later that day, Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke called Murkowski and the state’s other Republican senator, Dan Sullivan, to threaten that the Trump administration may change its position on several issues that affect the state to punish Murkowski, including blocking energy exploration and plans to allow the construction of new roads. ‘The message was pretty clear,’ Sullivan told the Alaska Dispatch News.

Nevertheless, Murkowski persisted. [Ed note: Oh James.] In fact, she took it one step farther and demonstrated that she has more leverage over Zinke than he has over her. As chairman of the Senate Energy and Natural Resources Committee, Murkowski indefinitely postponed a nominations markup that the Interior Department badly wants. [Ed. note: Including the nomination of this writer’s father.]

For their part, McCain’s and Murkowski’s votes allowed a number of other moderates – particularly Heller – to vote in favor of the legislation without risk that it would actually become law (itself an absurd statement, but YMMV). They will point to this vote next year as a representation that they tried to repeal, but also that they didn’t touch Medicaid. It’s amusing to think about a counterfactual in coverage of this vote if the three votes involved had been Cruz, Lee, and Paul – all of whom had huge misgivings about the approach. There’s a marked difference in tone to the coverage today, one that you certainly don’t see when intransigent conservatives blow things up.

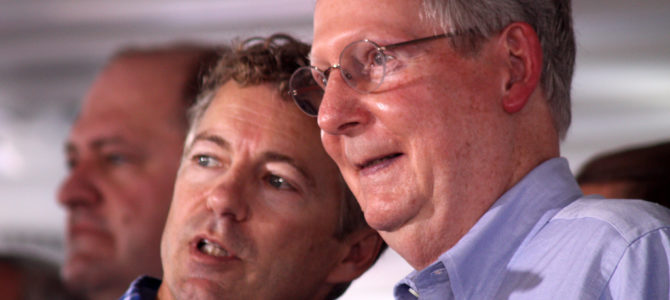

As a larger matter, the biggest loser in this process is the Majority Leader, Mitch McConnell, who did this his way, worked at it for months, and could not find a path through. McConnell’s attempt at skinny repeal was itself a last ditch effort to create a vehicle to go to conference, and an admission that this top-down approach to leadership of the Senate had failed. There just was not trust on the part of a number of members that this legislation, flaws and all, would not be jammed through the House if a conference failed to produce a result.

Ben Shapiro writes.

This is a major defeat for Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-KY), who after 7 years of promises wasn’t even able to get small changes to Obamacare past his caucus. It’s also a major defeat for President Trump, who wanted a major bill he could call his own, especially given the similarly uphill battle of crafting and passing a tax reform bill.

On the other hand, it also means that Republicans won’t pass an unworkable bill in the dead of night, call it a repeal, and then own the fallout – a fallout which would likely necessitate massive bailouts to insurance companies, given the reality of the pusillanimous moderate Senate Republicans. And this won’t be the last attempt to repeal Obamacare; as things get worse, calls for a Republican fix will grow louder.

Three main points quickly emerged after the GOP’s seven-year effort to kill off ObamaCare seemed to die a final death: the need to have bipartisan committee work, a desire to stabilize insurance markets and calls for administration action to change the healthcare law. Sen. Lisa Murkowski (R-Alaska) — one of three Republicans to vote against the so-called skinny bill, said she talked to Sen. Lamar Alexander (R-Tenn.), the chairman of the Senate health committee, on the floor, and he is already putting panel staff to work. Thune also said Alexander and his ranking Democrat, Sen. Patty Murray (Wash.), could work on fixes to the healthcare system in committee.

The skinny repeal bill would not have been repeal and replace any more than the work of these committees. And health care reform via some reconciliation vehicle is still not dead – McConnell has returned the bill to the calendar, which means he could potentially bring it up again if he got 50 votes. Getting there would require crafting a better piece of legislation with buy-in from all quarters. But that would require a Senate and an engaged president working together to get something done – too tall an order in today’s Washington.