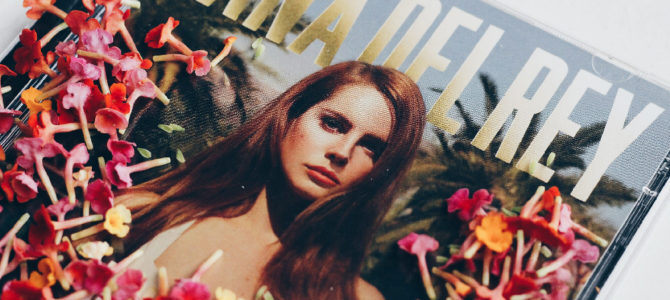

Lana Del Rey’s new album, “Lust for Life,” is scheduled to release on July 21. I’m looking forward to it; she hasn’t yet made anything I haven’t loved. For the longest time, I thought she was just some other pop star who couldn’t sing, getting by on her pretty face. I’m glad I’ve had the chance to correct that error of judgment.

There are a lot of misunderstandings of this woman and her work. One of the more wacky articles I’ve seen suggests Lana is a “pseudo-suicidal beauty queen” and complains she only sings about taking her clothes off without actually doing it. In-ter-est-ing: if he wants to see her naked, he could’ve just said so.

Most folk seem to be either too dazzled or confused to say anything intelligent about her. So here’s my best shot.

About Lana Del Rey’s So-Called Morbidity

It’s true that Del Rey talks about death a lot. Her first formal album, after all, is called “Born to Die.” But to call her morbid as if that were a bad thing is to fundamentally misunderstand where she is coming from. In a way, being born to die isn’t all that different from being born to run (Springsteen, of course). It can just be seen as the more passive, or feminine, side of the grand mystery of existence.

From the perspective of the soul, death is a door that opens: death and resurrection are two sides of the same coin. A “morbid” obsession with death can thus also mean a deep hunger for the true life. The soul sees these things not under the sign of contradiction but rather of paradox.

The paradox of death and resurrection is, of course, at the heart of the Christian gospel. Other traditions also say much the same thing. The ancient Stoics always maintained, for example, that to do philosophy is to learn how to die. And Sallie Nichols has interpreted the Tarot as a map of spiritual development. The Hanged Man is a key card of the Tarot, as is Death. But this sequence ends with the World, which features a dancer who has attained full self-mastery and realization of soul.

The gist here is that only by passing through your own death, like Christ through the cross of Calvary, will you come alive as an integrated human being. This is not “suicide” in the literal sense of the word, although it can seem that way from the perspective of the ego, given that the ego can’t tell the difference between transcendence and annihilation. To think hard about death is to knock on the door to the other side—which is the same as really trying to figure out what this human condition is about. If that makes one morbid, then by all means, sign me up.

Paradoxes of the Soul

Del Rey does use explicit lyrics. In one song she sings of her genitals tasting like soft drinks, and in another she calls herself a “bitch” and says all she wants is “money, power, glory.” But this is the furthest thing from the verbal pornography that characterizes so much of music these days. There’s an ironic, even tragic cadence to all of her words.

Consider, for a moment, that this woman also has a song (featured in the new Gatsby movie) in which she wonders, “Will you still love me when I’m no longer young and beautiful?” You can’t understand Del Rey’s work if you neglect one of these two poles.

This is the same tension that can also be found in the work of the songwriter Hozier. He does sing about falling in love with someone new every day. But then, he’s also none other than the man who has the sheer spiritual audacity to affirm: “When my time comes around / Lay me gently in the cold dark earth / No grave can hold my body down / I’ll crawl home to her.” There’s a bipolar dynamic to Hozier’s music, just as there is to Del Rey’s music: a bipolarity that is not a matter of personal idiosyncrasy, but rather a structural feature of the soul.

The soul is caught between time and eternity. This is its condition and its plight. We humans are also caught halfway between beast and angel. What mere reason understands to be opposites, the soul unites within itself through the form of paradox. Creative artists are often the ones who feel this paradox in its fullest force. That’s why they can also sometimes seem amoral: the mysteries of the soul often surpass narrow rational categories of right and wrong. To judge their work in a moralistic way is to altogether miss what they’re trying to say.

The Brothel Called This World

In a short film called “Tropico,” Del Rey starts off in a bizarro version of Eden. A little later on, there’s the Fall. The next time we see Lana, she’s a whore in a brothel. This isn’t primarily meant to be sexy (although I doubt any straight man could avoid at least thinking about that). Rather, this shift is emblematic of the humiliation of sin, especially as experienced by a woman: losing her spiritual liberty and becoming an object to the people in her world. Lana’s more than this; she’s a soul fallen from the Garden. But this world does not care, and for the time being, she’s stuck in a brothel.

The vision of this world as a brothel hearkens back to the prophecies of William Blake. According to Blake, the Fall was first and foremost characterized by the corruption of the imagination, one consequence of which is living in a world split into subjects and objects. In mythical terms, man is the perceiver, and woman is the perceived—but the deeper problem is that a schism between subject and object exists in the first place. Intuitions of the Kingdom of Heaven begin with the deep sense that things weren’t supposed to be this way.

More generally, the brothel is a good symbol for a world governed by sheer egotistical self-interest, where other people are seen first and foremost in terms of what they can do for you. Whoring is more a logic than a specific practice: the logic of never comprehending another person as a subject, only ever seeing her as an object who exists for your sake and not on her own terms.

This explains the self-deprecating tone of many of Lana’s songs: if she adopts a persona, it’s the persona of a sinner. As a beautiful woman, she expresses this in the body’s own strong terms—hence the sexual streak that runs across her work. But it’s impossible to hear her as actually celebrating lust for power, promiscuity, or whatever else. Rather, it’s almost as though she pretends to be a whore, embracing sin in an ironic way, as a means of getting to the heart of its mystery.

Or is it “pretending”? That’s probably the wrong word for it. It’s more like she’s living it through. I think of the awesome Parable of the Prodigal Son, where the father is more joyous over the namesake than the son who was just “good” the whole time. I also think of Jesus saying he came not for the righteous but for the sinners; I think of his terrible denunciations of the Pharisees. If death and resurrection are not opposites, then perhaps neither are sin and redemption. At any rate, that’s the language of the soul, which seems to be Lana’s native tongue.

An Ancient Tradition

In an interview Del Rey has said she only listens to Leonard Cohen, Bob Dylan, and Frank Sinatra. If that’s not true, it may as well be. Sinatra for the mood and style, I guess. But her content is very much up the visionary alley of Cohen and Dylan. The worst thing to do with such artists is to insist on interpreting them in a literal or political manner.

Del Rey is probably an anti-feminist. But that’s not relevant. The real point is that she would be an anti-feminist by neglect, as opposed to holding an affirmative position on the thing: it’s all just supremely uninteresting to her.

From the perspective of the artist, politics is a pretty silly thing to get all worked up about. That’s because art is an ancient tradition with a religious genesis. A given political situation thus becomes nothing but a prism through which certain aspects of eternal human nature are refracted with special clarity.

There is a sense of irony and levity to it all, like when Lana announced she was casting a spell on our current president. I don’t care what your politics are, if you didn’t burst out laughing at that, this is a sign that you’ve confused the secular for the sacred; politics for art.