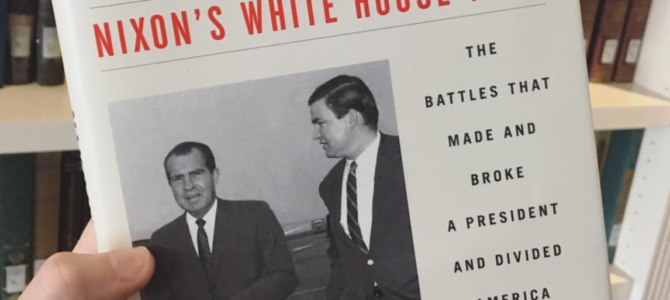

In a two-part interview series on the Federalist Radio Hour, Ben Domenech interviewed Pat Buchanan on his new book, “Nixon’s White House Wars: The Battles That Made and Broke a President and Divided America Forever.” They discussed his years as an advisor to Nixon, as well as Buchanan’s own political career. You can read the transcript here or listen below.

| Ben Domenech : | Boys and girls, we are back with another edition of The Federalist Radio Hour. I’m your host, Ben Domenech. We’re coming to you from Hillsdale College’s Kirby Center in Washington D.C., where today our guest for the full hour is Pat Buchanan, who is joining us to talk about his new book Nixon’s White House Wars: The Battles That Made and Broke a President and Divided America Forever. I want to thank you so much for taking the time to join us in the studio today, Mr. Buchanan.

|

| Pat Buchanan: | Delighted, Ben. You’ve got that NPR voice.

|

| Ben Domenech : | I was on NPR this morning so I should hope so. I want to talk to you about this book, obviously, and about President Nixon and everything that you write about in it, but because we haven’t had the opportunity to talk to you on this program before, I really wanted to start with you and where you came from. You’ve been an incredibly figure in terms of your impact on the right, not just as someone who worked in The White House for both Nixon and for Reagan, but also someone who had incredible impact on the conversation about the rise of American populism and the changing nature of conservatism in your lifetime, but you began in a position that I think few would think would be a starting point for the type of career you had. You began as a rabble–rouser in the streets of Georgetown, didn’t you?

|

| Pat Buchanan: | Well we grew up, actually, in northwest D.C. I grew up in a family of nine children, a Catholic parish up there, right up by Chevy Chase Circle. My father was a very tough character, great admirer of Joe McCarthy and General Franco and General MacArthur. He was a very dominant figure. He taught his sons how to fight because he expected they would be in a lot of fights and a lot of scrapes. He didn’t have any problem with that. Even when I was a pretty small kid and pretty thin and small he had you in the basement hitting the punching bag, about 100 with the left, 100 with the right and 100 with the 1, 2.

|

| Ben Domenech : | I’m just trying to think of what it must’ve been like to grow up in such an environment compared to the one that currently inhabits this town. How have you seen D.C. change in your lifetime?

|

| Pat Buchanan: | D.C. was a wonderful town to grow up in. We grew up in something, and I don’t mean this is in a derogatory way, of a Catholic ghetto. Everything was connected to Blessed Sacrament Church and Parish, School, CYO games, CYO dances. Friends I knew were all Catholics who I went to school with. They’d go to Blessed Sacrament and then down to Gonzaga or Georgetown Prep or St. John’s, which was right next door to our house. It was a community in which you fit in, you belonged. In that sense, there was a very good feeling about it. Your home church, everything, were very hierarchical. I think that had something to do with shaping who you would become, as would the nuns. I only had nuns for eight years and had only Jesuits in high school and almost only Jesuits at Georgetown University. They were different Jesuits than the current Holy Father in Rome.

|

| Ben Domenech : | Different in a lot of ways, I would suspect.

|

| Pat Buchanan: | You would be exactly right.

|

| Ben Domenech : | You come out of that and you decide to go into the field of writing, of journalism. Tell us about the odd path you took to meeting President Nixon.

|

| Pat Buchanan: | Well, when I was growing up here we used to look for jobs, all the high school kids, in the summer, a lot of times after we got off the playgrounds and things. A friend and I went out looking for jobs as caddies at some of the country clubs out at River Road. A friend of mine and I got at the Burning Tree Country Club and we were the last two fellas on the caddy log. As I used to say, we integrated the caddy log at Burning Tree. One day, late in the afternoon, we hadn’t gone out. We hadn’t carried a bag out, which is where you made your money. They put out the bag of the Vice President of the United States, Richard Millhous Nixon. Pete Cook and I went around with him for 18 holes. I carried the bag of some general whose name I forget, but I stayed very close to Nixon and listened to all the irreverent comments he was making to other folks, Senator Stu Symington. I remember that very well.

|

| “Hey Stu, there’s a vote up on the hill,” he yelled across the fairway. Stu told him what they could do with the vote. I said to myself, “My Lord, that’s Sanctimonious Stu, the fella Joe McCarthy’s been talking about.” I grew up in a town. It was a larger town in terms of population, 800,000, middle class, working class, white working class, divided evenly black and white, but a great place to grow up. Then after I had an altercation at Georgetown and went to work for my father for a year doing accounting, I went back to school and decided I would spend a year at the Columbia Graduate School of Journalism if I could get in, to see if I could become a journalist.

|

|

| I didn’t type. I didn’t write anything on college or student newspapers, but was heavily opinionated. I did very well academically. I got a $1,500 economic writing fellowship which covered my tuition fully. I made enough money working for my father so that I could take care of all this, and went up and lived in the International House, quite an experience up in New York, while I went to journalism school which was a phenomenal experience.

|

|

| Ben Domenech : | How much do you think, looking at the attitudes and the actions of people on campuses today, that you look at that today, the experience that they’re having in the Ivy League, this collapse really of a belief in the ability of people to have opinions without it necessarily being an act of violence or something along those lines. Did you experience anything like that at the time that you were in school?

|

| Pat Buchanan: | No, not in college. You didn’t talk back to teachers. A matter of fact, you didn’t talk politics in the courses I took, English and history and theology and philosophy and French and courses like that. No, there was no resistance to the administration. We got in trouble at a couple of the dances there. I got thrown out of the school. They didn’t fool around with you then. When I got to Columbia there really wasn’t anything that like when I was at Columbia Journalism School, ’61, ’62. I tell you, when I got into it I got a great job. I wrote to a number of papers when it’s only nine months to a master’s degree. The St. Louis Globe Democrat answered back and they offered me a job, starting reporter doing obits and things like that, but within six weeks an opening had come. I’d done some reporting after the obits. Then an opening came on the business page because I had an economic writing fellowship. Then there was an opening on the editorial page. I went back and applied.

|

| Six weeks there and they chuckled and said, “You can write editorials until we hire a new fella. We’re working on that now.” I was writing three and four editorials a day. This copy was all piling up. When they hired the new fella they kept me as the junior fella and the other fella went back to the newsroom. I was an editorial writer at 23 years old, I think the youngest on a major newspaper in America. It was a great time and a great place. It was a very conservative newspaper, fighting conservative, even moreso The Chicago Tribune in those days. Dick [Amberger 00:08:10] was the publisher. I fit right in on his editorial page.

|

|

| I’ll tell you, by early ’64, ’65, ’64 I wrote the editorial on Mario Savio at Berkeley and what had happened there. In ’65 I was being invited out to teach-ins at Washington University. While they weren’t violent, they were very bright. The kids knew a great deal about Vietnam. They argued it from a point of view of history and national interest, but I did very well at these teach-ins. After I would speak and they would say, “Everybody line up to ask somebody a question,” the big long line would come for me. It was all adversary position, but it was a lot of fun. Go ahead.

|

|

| Ben Domenech : | You came to enjoy that kind of combativeness, it sounds like, at an early age.

|

| Pat Buchanan: | Well, I mean I found that I enjoyed it and I was pretty good at the repartee, probably from my experience at my father’s dinner table. Yeah, I did enjoy that. I thought I did better at that than I did at standing and speaking the original speech, but after the Goldwater debacle I got to feeling that I wanted to be in on the action because it was very active decade. People were involved. I used to take my time off when I came back to Washington to see my family. Once I came back in ’63 and my brother and I went down to the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. I was about 15 yards from Martin Luther King when he delivered that speech. The next year I went down to Philadelphia, Mississippi before they found the civil rights workers. I can remember being in Meridian where the American flag was upside down in the town square the day the Civil Rights Act took effect. It was around July 3rd or 4th. Then we drove over to Anniston, Alabama and the Birmingham church.

|

| Each summer I would come home and try to do something, getting involved. I would ask the editorial editor if I can go to some of these places. You wanted to get involved in the action. I thought after Goldwater, I looked at it and I saw what Sorenson had done. You’d always see these figures when you’re very young. He’s sitting right there with the President. Since I grew up in D.C. we had no votes, no elections, anything. I wasn’t going to run for anything. I said, “Now that would be neat.” I liked Nixon. It was Nixon or Romney. I said, “One of these two is going to get it.” I was impressed with Romney, but I liked Nixon because of the connection, because he was an anti-communist and because he had stood by Goldwater.

|

|

| We got a lucky break. There was a cocktail party at Don Hesse, who was the editorial cartoonist, at his house. Nixon was going to come there after he spoke in Belleville. I think he filled in for Ev Dirksen. I went up to him around midnight in the kitchen and said, “If you’re going to run in ’68 I’d like to get aboard early.” I said, “We’ve met before, Mr. Vice President. You had the plaid golf bag.”

|

|

| Pat Buchanan: | John Sailor was the deputy pro. It gave him all the credentials so that he wouldn’t think I was bluffing him. An hour long trip out to Lambert, St. Louis with Don Hesse, coming back home from Belleville, Illinois, Hesse came into the office and said, “He talked about you the entire trip.” I waited, it must’ve been 10 days, and I got a phone call. “Would you like to come up to New York?” I went up to New York and spent three hours in his office. He hired me on the spot for a year. He said, “Unless we do well I’m not running in ’68,” because he believed in the strong base of the party. If it wasn’t there the nomination wouldn’t be worth anything. He said for one year and I’d write a column with him. I’d do all his mail, get that cleaned up and do all these chores, basically, but when he got in there he was sending memos into him from …

|

| We had an office. My office was right next to his. In the office was Rose Mary Woods, who’d been his press secretary since his case, and a lady called Miss Ryan, who Patricia Thelma Pat Ryan Nixon. I was a heavy smoker in those days. She’d give me cigarettes when I ran out, lovely lady.

|

|

| Ben Domenech : | It’s an incredible path though, in the sense that this is almost happenstance that you …

|

| Pat Buchanan: | Fortuitous, it sure was.

|

| Ben Domenech : | I’m curious, just before we get into your book, which is Nixon’s White House Wars, which follows on your book The Greatest Comeback, which describes a number of different things, historically, that I think are worth noting as well, but you changed the way that Nixon communicated in certain ways. What is the difference between Nixon before Buchanan being there with him at his side, both sending in these news clips to get the news to him but then also changing his message in certain ways? How did you change him?

|

| Pat Buchanan: | I think, well first I was a Goldwater. Nixon was suspicious of the right. They had chopped him up in 1962.

|

| Ben Domenech : | You quote him as saying, “The Buckleyites are worse than the Birchers.”

|

| Pat Buchanan: | Worse than the Birchers.

|

| Ben Domenech : | Yes.

|

| Pat Buchanan: | I had to clean up that to begin with.

|

| Ben Domenech : | I thought so.

|

| Pat Buchanan: | You see, the Nixon people who weren’t in the office, they were gone, but they were very anti-right wing. They were anti-conservative. They were anti-Goldwater because of what the candidate in California, Joe Shell, did in the 1960 campaign when the Birchers chopped Nixon up. Remember the Council on Foreign Relations chopped him up badly when Nixon wanted to run for governor. At the time the missile crisis had gone to a terrible defeat. A lot of those folks blamed the conservatives. When I got with Nixon I explained to him, I said, “I know 1960 you went up with the pack of Fifth Avenue to meet Nelson Rockefeller and try to put together a ticket with Rockefeller Nixon,” but I said, “The center of gravity of the party, they didn’t win the presidency. Center of gravity in this party has moved to the right. These are the grassroots people who controlled and took over the nomination.” Now if you put together the Nixon [sic] and the Republican party and bring in the Goldwater-ites, you’ve got it. Rockefeller’s not going to win the nomination. There’s nobody to your right.

|

| The materials I wrote for Nixon were basically conservative, anti-LBJ. They were traditional conservative. I would say national review conservative, except I will say Nixon was very strong on civil rights. I mean, we really ripped into Wallace and those folks in the columns we wrote as I had done in editorials, but Nixon, his credentials in foreign policy, the fact that he had gone out and fought for Goldwater and going down to defeat with Goldwater. We’re campaigning harder for him than Goldwater campaigned for himself, which was a natural thing Nixon did, but the right thing to do in his own interest. In January of ’65 Barry Goldwater said, “If you run again I’m with you. I’m completely with you.” Now we Goldwater and we had Nixon. The other side had Romney was their front man. They were going to send him in first.

|

|

| As I’ve told, Nixon made four critical decisions after his infamous last press conference in ’62 in California that really got him the nomination of the presidency. The first was calling Barry Goldwater, after he’d been at that Cleveland Governor’s debacle, and was trying to stop Goldwater and say, “I’d like to introduce you at the convention, speak for you at the convention and campaign for you for the election. This thing’s over. You’ve won it fair and square.” He did it and Romney and Rockefeller took a walk. The next thing he did was in ’66 when he hired me. He had made a decision to campaign all over the country in every congressional district and state where they would invite him and campaign for all the Republicans in the great comeback, which he was predicting. Now a comeback was going to happen. We were down to 140 seats. Then that great comeback in ’66. Then the next thing he did was he stepped out of politics in ’67 and let Romney go out and start running. As he told me, “Let him chew on him for a little while.”

|

|

| Ben Domenech : | They did.

|

| Pat Buchanan: | The press. The truth was that Romney had a golden opportunity. He was beating Lyndon Johnson in the polls. He was leading in the polls in, I think, November, December of ’66, but by spring with the press following him around, quite cynical crowd … Nixon, he was traveling abroad, trips all over the world. I traveled with him to the Middle East 50 years ago now. Six-Day War, we came in there right after the Six-Day War. Nixon did all that and then he made the great decision, wise decision. He said, “I’ve got a reputation as a loser. Everybody calls me a loser. Okay, I’m going to have to start winning. I’m going to go in every single primary and take on all comers because you’re right. I have a reputation as a loser. I don’t deny it.” Nobody came into the primaries against him except for Romney. Nixon held up to the last day to get into New Hampshire. By the end of that month, February, Romney was sitting on his chair in the corner, not coming out.

|

| Ben Domenech : | You write in this book about, obviously, the experience that you had in the early days of the Nixon White House, when you saw basically a shift in the way that he was staffed and that a number of different people were put into positions that you thought were not necessarily reflections of the kind of promises that Nixon had made about what his administration would bring to bear. You document in the book about people like Alan Greenspan getting no offer that appealed to him, that people like Kissinger were put in much more significant positions. There was, of course, the Germans who took over and ran things. You look at that as a picture of a White House that doesn’t necessarily reflect the President.

|

| There have been a lot of comparisons made between President Trump and President Nixon. I would say the ones that have to do with scandal are irresponsible and inaccurate, but it does seem to me that he shares a lot of things in common with him. Do you think that this is something that’s also in common at the moment, that you have a White House that is maybe not staffed up to the level that it ought to be in order to fulfill the principles, promises?

|

|

| Pat Buchanan: | Well let me say about Nixon’s staff, Nixon created the staff structure he wanted and he had thought of since Eisenhower. He always wanted a strong Chief of Staff. The Chief of Staff would run the White House staff. It would be run as almost a military organization with The Oval Office protected, people not just walking in. That’s the job Haldeman did extremely well. My feeling was that as a conservative, I was the highest ranking conservative in that White House. I was the closest to Nixon, but he brought in Kissinger in foreign policy, he was Rockefeller’s guy, Moynihan in domestic policy. He did hire Arthur Burns, who had been Ike’s economic man, but Arthur didn’t have the skills of Moynihan. Cabinet officers, you’ve got George Romney, you’ve got Bob Finch, Wally Hickel and others. Basically what you had is establishment and moderate and liberal Republicans dominated in The White House in terms of policy and also in the cabinet. I was the strongest voice, if you read that book, coming from the right.

|

| Now what Nixon had though, that the rest of them in there didn’t have is Nixon recognized that the coalition we were trying to build, Goldwater Nixon Republicans united and the don’t drive the liberals off but they don’t run the show. The establishment there, they don’t run the show, and then reach out to the conservative, the Catholics, the northern Catholics and the southern Protestants who had gone for Wallace and Nixon. We split 10 states between us, the Confederacy and Humphrey got Texas. My feeling, what I came down to is, Nixon himself was fundamentally a progressive Republican in the T.R. tradition who was not hostile to a lot of things done in The New Deal, but in his political strategy and his rhetoric and his presentation of the country, very much populist, anti-establishment, denouncing the demonstrators. He couldn’t do what Wallace did so effectively, but in terms of a two-way race I looked at this thing and a number of times I’ve wrote, “Look, we’re going to split the country but we’re going to wind up with the larger half,” which is what we did.

|

|

| I think in foreign policy he was an internationalist. That’s what he really cared about. He said, “The country can take care of itself pretty much. You need a President for foreign policy and Henry and I are going create this generation … ” He was very much part Wilsonian in terms of his optimism and what could be accomplished. He believed in this generation of peace. Read his first inaugural. It is astonishingly liberal, his first inaugural, holding out his hand to those left out in America, reaching out to the world, “Let’s not have confrontation. Let’s compete.” He was a very complex figure, but I think that when you come down to a description I think those three best describe him as a political figure.

|

|

| Ben Domenech : | You recount a scenario in the administration where Pat Moynihan is fiercely defending LBJ’s approach to social policy and basically saying we can’t undo all these different programs that LBJ stood up, that the streets will be on fire, the ghettos will burn, that type of thing, but then particularly you have this one anecdote in the book, “When he went to Ehrlichman to protest that the Family Assistance Plan, the welfare program Moynihan had worked up, was antithetical to Nixon’s basic philosophy, Ehrlichman replied, ‘Don’t you realize the President doesn’t have a philosophy?'” That’s something that the say about Donald Trump too, that he’s basically just someone who is transactional. He doesn’t have a particular philosophy, but it seems to me that there’s a lot of overlap. Do you see that as well?

|

| Pat Buchanan: | Well, I think that’s right. I think when he saw which way the Warren Court was going, he didn’t get along with Warren. He wanted people who would take the opposite view and not be interventionist and basically what I called strict constructionist which he picked right up on. I think he had a series of beliefs but none of which I think could not be pretty much discarded because I think he believed more in the idea of the great man making bold decisions and moving suddenly in a new direction. As Moynihan told him, “Tory men with Whig shirts.”

|

| Ben Domenech : | Yes, exactly.

|

| Pat Buchanan: | Moynihan sold him on the Family Assistance Plan with a guaranteed annual income. I think there’s some truth to it, to what Burns said. I’ve got my famous memo in there that really angered the President. Neither fish nor fowl that we present to the country … We’re going by this smorgasbord picking out this, that from the various philosophies. We’ve really got no deep following as a consequence of that. People both think we’re opportunistic and the truth was we were.

|

| Ben Domenech : | Do you look back on Nixon’s domestic policy as being something that was a real missed opportunity? You certainly describe his policy, his selections as it relates to the Supreme Court, as a missed opportunity in this book.

|

| Pat Buchanan: | The Court, they were not well-vetted, some of those judges we put up there. They were supposed to be vetted by Mitchell’s justice department. I think it was a real missed opportunity in terms of shutting down the worst of the great society programs. He not only didn’t shut them down, he funded them. I think when we came in, I don’t know, there were very few on food stamps. I think by the time we left five and a half years later it had quadrupled and things. All of these things, Medicare and Medicaid, but I think Nixon … Moynihan wanted to keep all these programs and Nixon was not so determined to get rid of them that he was going to go against what he was being told. I also think he knew that would be bad politics for him. That wasn’t the big thing. You give them that and hopefully they’ll give us some support in foreign policy and in building the ABM system that I can trade away when I get to Moscow.

|

| Ben Domenech : | You know, Nixon was a real strategist of America in the world in a way that we haven’t really seen since. Do you think that any of the Presidents that have come since measure up to him?

|

| Pat Buchanan: | I think that’s exactly right. Even Reagan once pulled me aside and said, “You know … ” Of course he had ripped up détente. He said, “Pat, Nixon had a pretty good foreign policy.” I think Nixon had a vision, partly informed by Kissinger, to the balance of power and also cutting big deals. His foreign policy, look at his first five years. Put in the fifth year. He entered into détente with the Soviet Union in the greatest arms agreement since the Washington Naval Treaty of 1922. He opened up China in an extraordinarily dramatic move. He realized that he had to move out of Vietnam and he sought to do it in a conservative way, leaving them with the enemy basically defeated and the south Vietnamese armed to the teeth but basically on their own. He did all that and brought all the troops home and brought the POW home. He flipped Egypt to the western side after the Yom Kippur War.

|

| I think that’s part of the whole thing. He would argue for an ABM system so he could sit down and deal with the Russians. All of this, I think it was very thought through. It’s what he really cared about. I traveled with him in ’67 for 3 weeks to the Middle East. He loved it. He was in meetings with foreign ministers and even African leaders. He’d patiently explain the policy of Johnson and defend it. As I said, he was like Dean Rusk over there. He loved that. You really saw him up close in his element which he really … He was a patriot. He loved his country. He was doing his best for it, but he did want to be a great man in history.

|

|

| Ben Domenech : | Yeah, he was mesmerized by that idea even at the same time that he continued to be treated very horribly by the press.

|

| Pat Buchanan: | That was awful.

|

| Ben Domenech : | You opened your book talking about his speech and talking about actually showing a program with Alger Hiss on it, basically showing the end of his political career, believing that they had gotten rid of him forever.

|

| Pat Buchanan: | Sure.

|

| Ben Domenech : | Then of course he mounted this amazing political comeback, but the attacks from the press and the media did not stop. It never really went away. You of course recount in this book, in Nixon’s White House Wars, about the role that you played in encouraging The White House then to fight back, to push back in a lot of different ways, particularly through the Vice President.

|

| Pat Buchanan: | Well, that’s the crucial month. The making of Richard Nixon’s presidency was not just ’68 where he got 43%, but 1969. That was the key moment. In October of ’69 we had a massive demonstration, some 250,000 expected on the Monument grounds. They asked me for some memo about how our PR operation’s going. I wrote him a memo saying, “The Presidency’s in real danger of being broken.” David Broder had written a column saying exactly that. I said, “If we don’t turn this around you’re going to be like Louis XVI. We’re going to be broken just like Lyndon Johnson was.” Nixon decided to give this speech on November 3rd. He gave it, The Great Silent Majority Speech, the most successful of his Presidency. When it ended it was ripped apart. It was a 9:00 speech but ripped apart by the 3 networks scoffing at it. These were the primary means of communication with the American people about national/international issues, two-thirds of them got their information from these guys.

|

| I sent him a memo which I think was the most important I’ve wrote in The White House, saying, “Now is the time. We’re going to have to go directly after the media and here’s the way to do it: a major speech by the Vice President, which I will write.” I worked and Nixon said, “Go ahead.” I’ve got the memo still at home, the original. He called the VP. On November 13th, 1969 in Des Moines, Agnew launched this attack on the networks for enormous power and bias which they were abusing to advance their own agenda and to destroy the mandate of the President. The three networks carried it live. It was unbelievable. Agnew was suddenly the third most admired man in America, the whole country. It shows you what the country was then. It’s much more divided now. We don’t have as many with us now, but then we had an enormous majority with us.

|

|

| Ben Domenech : | You write Agnew’s phrase, “Effete corps of impudent snobs, I told Nixon in my media memo of October 27th, had roughly the effect of dynamiting an outhouse next to a Sunday school picnic.” It seems to me though that there’s an obvious parallel here. You can definitely make the case that Nixon was persecuted by the press over two decades, really out of animosity towards his role as an anti-communist in the Senate and just moving from there all the way through his career, but his downfall was in part due to the fact that he lashed out in ways that provided them the means to destroy him. Do you agree with that idea? Is there any parallels now?

|

| Pat Buchanan: | No I don’t for this reason. People say, “You know, as Nixon found out, you can’t take on the press.” Nixon took on the press and defied the establishment. At the end of ’69 he was at 68% approval and 19% disapproval. Now, it was a different country, but in ’72 we got the candidate we wanted, the candidate of liberalism in the counterculture. We rolled up a 49 state landslide. Nixon had won. Nixon, quite frankly, was not always for confrontation. He would tell, “Shut down Buchanan and Agnew. They’ve done enough now.” He was not always for that kind of permanent war that Trump fights. It was much higher level, I think, battle than Trump fights. What happened to Nixon was the misjudgments, letting it get to him, issuing these orders and have some people carry out these stupid things, the bugging. I don’t think he knew about the original bugging, but after that, naturally saying, “We’ve got to take care of our buddies.” He had the tapes running. He’s involved in an obstruction of justice or close to it.

|

| I think those were the blunders that brought him down. You’ve got to realize at the end of his first terms he was a smashing success. He’s sitting up there at Camp David on top of the world. The left was going bananas after what he had done. He had slipped in that June and taped himself doing it. Things had been allowed by Haldeman. The taping system, I’ve sat in times in there with the old man when he’s having a drink and he’s carrying on. I mean, he’s having a good time just like a bunch of guys would. It’s all being taped and recorded for posterity?

|

|

| Ben Domenech : | Not very smart.

|

| Pat Buchanan: | Why didn’t Haldeman stop it?

|

| Ben Domenech : | On a fundamental level, do you view this as the failure of a staff to live up to what they needed to provide to the President?

|

| Pat Buchanan: | No, I mean, Haldeman was … He was one of the Germans. Somebody said, “Every president needs an SOB and I’m Nixon’s.” As I write, he was very good at this. I had real tensions with Haldeman and Ehrlichman constantly, the Christian scientists, the Germans, but I will say he ran an honorable shop in the sense that when I sent something over, a memo over, he disagree with, it went right into the President of the United States. Ehrlichman, you discovered after Watergate he was a very talented individual. That was the most talented White House I’ve ever worked in. I worked for Reagan and briefly for Gerald Ford. It wasn’t first division ball clubs.

|

| Ben Domenech : | Pat Buchanan’s new book is Nixon’s White House Wars: The Battles That Made and Broke a President and Divided America Forever. I’m Ben Domenech. We’ll be back with more of The Federalist Radio Hour right after this.

|

| We’re back on The Federalist Radio Hour. I’m your host Ben Domenech. My guest for the hour today is Pat Buchanan, who’s the author of the new book Nixon’s White House Wars: The Battles That Made and Broke a President and Divided America Forever. Just a funny anecdote from Evan Thomas’ book about Nixon, “I could be comfortable being a Catholic,” he told Chuck Colson. “Nixon admired the stability of the church and the depth of Catholic faith. One day in 1970 he asked Pat Moynihan, ‘You believe in the whole thing?’ Moynihan was his usual irreverent self. ‘Not only that,’ he replied, cocking his head at Haldeman and Ehrlichman, both Christian scientists, ‘I even believe in doctors.'” Tell me what you think about Richard Nixon’s faith, particularly how it influenced his view of his role in the Presidency.

|

|

| Pat Buchanan: | Well, I found that Nixon liked Catholics and admired them. The main influence there was Rose Mary Woods, who was a Catholic and had been with him for 20 years. He admired their loyalty and fighting spirit. About his personal faith though, I think he clearly thought about it deeply but I never sat and discussed religion with him. I wouldn’t be able to talk to that. I know he really, deeply admired the faith of his parents, how deep it was and how they lived their lives by their principles. In that memorandum he gave me to give to Peregrine Worsthorne, Nixon brought him in. I encouraged Nixon to bring in this British journalist who had written some wonderful things about him or good things about him and wanted an interview. Nixon brought him in and I sat in there while Nixon talked to him. Worsthorne had asked Nixon if he’d come into politics in the 30’s rather than the 40’s would he have been a New Dealer. Nixon gave an answer. It wasn’t complete.

|

| He wrote this long memo which is copied almost entirely in my book, saying that the values that had been inculcated in him because of the faith of his parents and their belief, for example, that they shouldn’t use public services unless someone was totally desperate, that was for other people, and how his two brothers died, young brothers. It was a horrendous experience. You go out to the Nixon Library and look at that little house with the ladder going up to the attic where they slept and things. In terms of personal faith, I don’t know. He certainly had a very close relationship with Dr. Billy Graham, a very buddy-buddy relationship almost. I remember Billy Graham invited us, come into this monstrous Graham rally at the Pittsburgh Stadium, I think, during a campaign, to basically give him his benediction, political benediction, but about his personal beliefs, I think he was tempted but I don’t know that he ever crossed the line and joined the faith.

|

|

| Ben Domenech : | One of the reasons, one of the little things that I took away about him is Whittier was one of the towns that refused to take New Deal money from Washington. They referred to it as Bolshevik to do so.

|

| Pat Buchanan: | That’s a Quaker.

|

| Ben Domenech : | Yes, and that’s something that’s ingrained in him throughout his life. You were obviously in the room for so many critical moments during his Presidency. You write in your book, of course, about the dinner with Barry Goldwater, near the end.

|

| Pat Buchanan: | The famous dinner.

|

| Ben Domenech : | Tell us a little bit about that dinner and what that experience was like.

|

| Pat Buchanan: | Well, Nixon was in very tough shape, unquestionably. He had gone through the Yom Kippur War. We had lost the Vice President. We had conducted the Saturday Night Massacre in October. Agnew’s resignation and Ford’s appointment all then, and then they had an oil embargo in the United States, the Arab countries did, because Nixon saved Israel. As Golda Meir said, “Richard Nixon’s the best President, friend Israel’s ever had.” He had these huge airlifts going over there and saved Israel. The Israeli army, General Sharon crossed the canal and everything, but a month or two later Nixon was really down. Goldwater had made some derogatory statements.

|

| Nixon invited him to dinner at The White House. Ray Price was there and I was there, Rose Mary Woods was there, Bryce Harlow was there and our wives. Barry was at the end of the table. Nixon had had a couple drinks. The subject turned to whether he should take a train from Washington to Florida down to his place in Key Biscayne. It would take him 24 hours. I said I didn’t think so. We couldn’t find all the troops to guard these tressles and everything, bridges. We were all laughing about that. Goldwater said, “Just go fly the plane. Don’t bother with that,” but Goldwater apparently was taken by the fact that Nixon was careless and he called Bryce Harlow the next day and Bryce apparently said he was drunk. I think Goldwater must’ve been the source for Woodward and Bernstein because Ray Price in his memoirs said he was not drunk and that Nixon was just enjoying company, pre-Christmas celebrations.

|

|

| Goldwater wrote in his memoirs in the 90’s that Pat Buchanan’s the only one that’s never talked about that. It was a stiff dinner in the sense that Nixon was saying, “Bryce,” in effect, “tell him what we mean,” etc., but what Nixon wanted, I think, was to make sure Goldwater … Just as I had said earlier, Goldwater represented the conservative wing of the Republican party. If you had Goldwater behind you, people wouldn’t vote but if Goldwater broke you would have real problems. When the Watergate tapes and things came out, Goldwater was very, very bitter about Nixon after that. We remained friends. I remember when I test … I just got it in my basement, found something that I found in the archives. After I testified Goldwater said, “I’m really proud of you,” like he’s your old man or something. It’s really wonderful. It’s a telecopy of a telegram, but I think he really turned on Nixon and has been very bitter about him ever since.

|

|

| Ben Domenech : | When you look at Donald Trump today, do you view the rise that he made as being a vindication of a Nixonian brand of conservatism, defeating the movement that never really regarded Nixon as one of them?

|

| Pat Buchanan: | No, I don’t see that. I think what Trump did, I believe, is Trump took the issues … What brought me into journalism and the key thing you’re writing about when I was your age and even younger and even older, the key thing that drove us all, to me, in the conservative movement … I bought into all the conservative philosophy and everything. Well, that was the Cold War. That’s the enemy of the United States that’s a mammoth military power. It’s unprecedented. It’s got an ideology against us. You’ve got to fight them. When the Cold War ended, that’s when I said, “What are you going to do, Joe, now that the war’s over,” they used to say during World War II. To me, I said, “These other people had been freeloading off us. If the Russians are going home and the Red Army’s going home and the Soviet Union doesn’t exist, the Soviet Empire doesn’t exist, let’s return to a traditional American foreign policy, America first.”

|

| Then I looked around and I had seen what trade had begun to do all over the country and go places. One factory after another’s been shut down so more and more. I was a free trader. He said, “Just a minute. There are casualties to these free trade policies I’m pursuing.” Milton Freeman wrote me a letter. He said, “You are doing the devil’s work.” Those are the issues now. Those are the new issues, the trade, immigration and America first and stay out of foreign wars. Those issues weren’t in the Nixon era. They were in the Nixon … You do have the populist thing I told you about.

|

|

| Ben Domenech : | Yes.

|

| Pat Buchanan: | Populist, anti-elitist, the snooty kids running around defying people.

|

| Ben Domenech : | Exactly. Does that silent majority still exist today and are they still a majority?

|

| Pat Buchanan: | Second question is they are not what were. We could roll up. We and Reagan rolled up 49 state victories. You can’t do that today. As I tell people, I said, “Ronald Reagan won four landslides in California, President and Governor. Nixon won the state six out of seven times he ran. Every time he was on a national ticket he won it.” You can’t carry California today. More than two-thirds of the Congressmen are Democrats. Governor, not a single state office is held. Two-thirds of both houses of the legislature, it’s gone. You can’t put together the great silent majority and run those mammoth landslides that came of Richard Nixon’s new majority coalition. That’s what Reagan rode to victory, the Nixon’s new majority coalition, but you can’t put that together again because of the demographic growth of the left since the 60’s. It’s grown and expanded.

|

| Ben Domenech : | It’s also changed.

|

| Pat Buchanan: | It’s culturally, socially, morally, the country is split.

|

| Ben Domenech : | The radical left, obviously, existed in Nixon’s time of course and was very vocal, but isn’t it very different from the radical left that’s resurgent now on a number of key points? Wasn’t it mostly then motivated by foreign policy and the culture war and now it seems to be almost a lockstep identity politics regime?

|

| Pat Buchanan: | I think that’s right, but what happened in the 60’s though was there were a series of revolutions. There was the women’s movement. You had the gay rights movement began in the 60’s at Stonewall. You had the civil rights movement which deteriorated into the riots and turned much of the country off, but all of these social, cultural, racial revolutions, if you will, they were majority on some elite campuses, but you are correct now. It is much larger, people that believe many of the things or the development of the ideas from that era. You do see on the campus now. It’s a religious movement. What somebody wrote once is that intolerance is the mark of a rising faith, not a declining faith, a rising faith. That’s correct, I think. I understand perfectly. These people believe that what Hillary said, “We are all racist, fascist, anti-Semites, homophobes, xenophobes, Islamophobes,” they believe it.

|

| Ben Domenech : | You have a quote in your book from Arthur Schlesinger, Jr. in response to Agnew’s comments, “The emotional power of his utterance comes from his success in voicing the hatred of the American lower middle class, for the affluent and articulate, for the blacks and the poor, for hippies and yippies, for press and television, for permissiveness and homosexually, for all the anxiety and interruptions generated by the accelerating velocity of history.” It seems like the left today is saying the same thing though, that basically all of this animosity toward the leftist culture war is just driven by racism and bigotry.

|

| Pat Buchanan: | Well what they do believe is … My views, let’s say, haven’t changed since the 60’s with regard to Right to Life, equality, all these things like that, but they do honestly believe, “If you don’t think Robert E. Lee statue should come down, what’s the matter with you? Are you some kind of racist?” They believe that. I think we’re talking past each other. I wrote once, when you take how many things we disagree on and how hard the disagreements are, that if America were a couple it would’ve divorced a long time ago.

|

| Ben Domenech : | You mentioned these Confederate statues. This is obviously one of the things that seems to me to be new about the left in the sense that this attitude of iconicalism toward the past, that the past is a different country that must be destroyed for us to continue living. It doesn’t seem like there’s going to be any stop to that though. It seems to be accelerating.

|

| Pat Buchanan: | They believe that America was born out of … America’s not the good country … I mean, we took for granted we were the greatest country in the world. You grow up as a little kid from three to seven years old, World War II, the United States is defeating everybody all over the world. We’re the heroic people. We saved the world. We believed it was a good country but they believed that it was, even in its roots, it’s the product of a poison tree and poison roots, that Columbus and all these people were racist coming out of Europe to impose their alien faith upon these indigenous people, that they brutalized them, enslaved them. They brought slaves here. They did all these, the Indians, they annihilated the Indians.

|

| The whole creation of the country and the people, obviously, the slave owners, all the southerners were that until 1865, or most of them. All of these things make the roots of America rotten so that America’s basically is a product of horrible things and it’s a better country now but these people have to be extirpated from our memory, from our history. People have to look to people like Dr. King and others for when America really became a good country. There are flaws and failings in the founding fathers, in all of those people, but I mean, that’s our history.

|

|

| Ben Domenech : | It’s not something that we’re better off for forgetting.

|

| Pat Buchanan: | I mean, there are bad things done but it’s a phenomenal history. I mean, all the Greeks all had slaves. The Romans did horrible things, but they created the greatest civilization known to man. Western civilization is the greatest civilization. I believe in Charles Murray no matter what Middlebury says. I mean, he’s got all these statistics near the Ark and the architecture and the paintings and the government institutions and all the rest of it. They’re products of western man. That’s my civilization.

|

| Ben Domenech : | Pat Buchanan’s new book is Nixon’s White House Wars: The Battles That Made and Broke a President and Divided America Forever. Friends, we’re going to be doing something that we never do on The Federalist Radio Hour. This one’s a two-parter. We’ll have more tomorrow with Pat Buchanan. I’m Ben Domenech. You’ve been listening to another edition of The Federalist Radio Hour. Until tomorrow, be lovers of freedom and anxious for the fray.

|

Part II

Read the transcript here or listen to the full episode below.

| Ben Domenech: | All right boys and girls, we are back with another edition of The Federalist Radio Hour. I’m your host Ben Domenech. We’re coming to you from Hillsdale College’s Kirby Center in Washington D.C. where my guest for the hour today is Pat Buchanan whose new book is “Nixon’s White House Wars: The Battles that Made and Broke a President and Divided America Forever.”

|

| So we’ve talked a good bit about Richard Nixon in our previous episode, and I wanted to continue this conversation but talk a little bit more about you. So you worked for Nixon. You worked briefly for Ford. You worked for Reagan. And then despite the fact that as you say in this book that you realized that you had a talent for the writing and the arguing part of it, but didn’t necessarily view yourself as the principle. That changed. You ran for President. You made a great deal of noise. The pitchforks were out en masse. And that culminated in your 1992 address to the RNC, which I would put alongside things like the Moynihan Report and Solzhenitsyn’s Harvard Address as being things that you must read in order to understand American politics.

|

|

| You have to feel vindicated in a lot of ways about that speech, which warned of a culture war that was coming. One that ultimately, I feel like, was lost. How do you think of that speech in today’s context? Do you think that it was basically right?

|

|

| Pat Buchanan: | Oh I thought it was basically right at the time. Actually the initial reaction in the polls and in the hall it was tremendous and in the polls. What happened as a consequence of that, the backlash from the left was extraordinary. And they attacked it and attacked it, until President Bush and Jim Baker ran away from the ideas. And I sent a memo to Jim Baker in September, no I guess it was … Yeah September I believe, or maybe it was late August, saying “Don’t run away from these ideas. They’re the only ones that can win for you.” And the reason was, on the economy 16% of the country thought Bush was doing a good job. You don’t talk about the economy. And foreign policy was off the table. And these were the vulnerabilities of Bill and Hillary Clinton. They were out of touch with middle America. And if Bush had made that case, I believe he could have won.

|

| But no, I’m very proud of that speech. As I look at it now, you know it’s pretty temperate in the way it’s delivered. But let me tell you how it came about is after the California Primary, I stayed in through California. I was taken right to the hospital, and I had open-heart surgery. It had been prepared. And so that was around June 6th, something like that. And my sister went to negotiate … I told them, the Bush people will come to us. We got three million votes. They don’t come to us, they don’t come to us. So they came, and they called up Bay you know.

|

|

| So they offered me a slot on the second night with Phil Gramm, and Phil would give the, what is it? Opening speech. Supposedly, but it’s the second night. And so Kemp got in and you know, Buchanan’s not doing that, and so he took my spot. And so Bay said, if we’re not in primetime, we’re not doing the speech endorsing you. So they said, the only thing we’ve got is this first speech on opening night before Reagan. And Bay said, “Oh that will be just fine.”

|

|

| But you know what we did, I went out and she got a thing. I’d never read a … I think I’d only read a teleprompter once or something. She got a room somewhere out in McClain, and I would go in there, and my problem was I didn’t have any strength. You know after that heart surgery, I was weak. I couldn’t walk or do anything. And you don’t have the strength to really get up and deliver it.

|

|

| So we worked on it every day. I was out there delivering it, and we got down there and it was a phenomenal experience. I went into this stadium. So the fellow that was up on the podium, he said, “Now Pat, when you deliver your speech, you’re going to look to the left there’s 15,000 to your left when you look over there. When you look to the right, there’s 15,000 over there. And you can see all these cameras down the middle, there’s 20 million right down there. So when you speak, and when you get to your best lines you just look straight down that middle camera.”

|

|

| And so I thought it came off extremely well. You know all the talk about it being a divisive speech, George H.W. Bush phoned me. Shelly sat in the box with Mrs. Bush and everything. They were all enthusiastic about it, and I think the reason Bush is not President is he’s not comfortable with those ideas, and when he gets pushed on those issues they move off them. They just won’t stay on those, because they don’t down deep really believe them.

|

|

| Ben Domenech: | Well, and also because the consultant is in their ear saying, “Well don’t say something silly.” But it always seems to me that in politics, if you don’t defend yourself, that’s much sillier than saying something that’s wrong. It’s much worse to not offer anything.

|

| Pat Buchanan: | Yeah. But let me tell you something about Ford. The guys came to me after I’d written Agnew’s speeches, and Ford was running. He had beaten Reagan. I was with Reagan out in Kansas City. And they came out to me, and they brought me up to the Metropolitan Club, and they said, “Ford hasn’t got an inch of good press. Do you think we ought to really turn and take on the press?” And I said, “I think you’re gonna have to, and I think you ought to.” And then I thought of it and said, “No. Don’t do it, because he doesn’t believe it.” It’s not inside, and as soon as they come after him, he’ll run away.”

|

| Ben Domenech: | So back to your address, one of the things that your address has in common with The Moynihan Report with Solzhenitsyn’s Address, is that it’s basically borne out by events. That it says, look at this thing that is coming. This is what is going to happen, and then it’s borne out. But one of the other things it has in common, is that it doesn’t change the trajectory, really. It’s a warning, but it doesn’t actually change the trajectory.

|

| Pat Buchanan: | Well, you know that’s why people said, “Buchanan declared culture war.” I didn’t. You described culture war, what is coming, and you had Hillary’s agenda. But I look at Hillary’s agenda, it’s all been enacted into law. You know? And after I gave that speech, Irving Kristol … Irving Kristol and I have been good friends, back in the early Nixon years, and he wrote a piece in the Wall Street Journal, and he said, “I regret to inform Pat Buchanan that the culture war is over. We lost.” You know, and I think he was right.

|

| Ben Domenech: | The thing that’s interesting though about culture wars is that there’s always that moment of overreach. Where the kind of ascendent majority, or the type that feels like they’re currently holding that position, will try to do something either via law or via politics that seems to go too far, and prompt a backlash. Do you view Trump, and there’s all these sorts of descriptions of why he happened, but isn’t he on some level, completely an example of what happens when people feel like that culture war overreach is happening, and is coming for them?

|

| Pat Buchanan: | Well exactly. Trump is not only that. People see the behavior, and what they’re doing, denouncing Trump and the violence in the streets and people marching under Mexican flags. There’s no doubt there. But also, it was the new issues. The new issues of trade, economic nationalism, economic patriotism, ethno-nationalism to a degree, America First. All of these things said that Trump, I am not one of them. And people rallied to him, and I felt it myself. Look, the Billy Bush thing was a horror show. But you say look, I’m not going to be driven away from the last chance we got, basically a lot of people, to save the Republic because of his behavior. You’re not going to let that happen.

|

| But let me say this, I might disagree with you here. I really believe that the West is very probably in a terminal decline. I mean it’s lost its faith. It’s lost its empires. It’s losing its unity now. It can’t defend its borders. It’s demographically dying. And you look at all these trends, and I wrote in “Death of the West”, I mean T.S. Elliot has a great line about … Was it Elliot? Anyhow when the faith dies and these various things happen, it takes a long, long time before these things grow back up again.

|

|

| I mean you take the Roman Empire when it went down. Christianity slowly took over, and people say they call it the Dark Age, but people woke up in all this wonderful world they were living in, you know?

|

|

| Ben Domenech: | It’s not so much that I would disagree with you, as I would just say that if you are a believer you believe you’re always on the wrong side of history. So it seems-

|

| Pat Buchanan: | What was that great line of Clara Boothe Luce used to know, that “There are two kinds of people in this world, the optimist and the pessimist. But the pessimists are better informed.”

|

| Ben Domenech: | It seems to me though that you emerged from 1992 and that experience with a great degree of momentum around a defined idea of kind of a different direction for conservatism. One that obviously sparked controversy and backlash but also that clearly had some things that it stood for. You build around that and run again in 1996. Why do you believe that the message that you had then didn’t necessarily receive the kind of political momentum that future populists movements on the right have? Do you think that there was something wrong about your approach, or was it just that the party wasn’t ready enough to embrace these ideas? What was it?

|

| Pat Buchanan: | Well we won New Hampshire, and I won Alaska, Louisiana, and we knocked Gramm out of the race in Louisiana. And we came up to Iowa, and I was three points behind Dole. I said, if I knock the old man down twice, if I beat him in Iowa and New Hampshire, I could have beaten Lamar for the nomination. So we did make it. But I ran second. I think I got close to three million votes again. The one thing I do believe, and where Trump succeeded, is what we predicted in 1992 and ’96 about the manufacturing decline of America, about staying out of these foreign wars, and all of these things, and also securing the border.

|

| We went down to the border in 1992, and they’re coming across the border 5000. My father took me down to the border. All of these issues really matured because of what happened in the country. So when Trump got up, he could say we’ve lost 55,000 manufacturing jobs in the first decade of the 21st Century and six million jobs. And he’s got it. So the people will say yeah, I see it right down the street. So I think that’s one of the main reasons is, we were predicting what’s gonna happen if they followed these policies. And they followed the policies, and it happened. But when they did, I was watching television, watching Donald Trump.

|

|

| Ben Domenech: | Do you regret in any way that this form of populism had to find its vehicle in someone like Trump? In the sense that it’s been around for a while. It’s had different vehicles, but this was the one that finally worked.

|

| Pat Buchanan: | Well, nobody really picked up on these issues. And I will say when Trump came down the elevator, and he started talking about the border. And you saw that the things he said … Look clearly he’s inexperienced in politics, but he has assets, and he’s got a certain toughness to take a beating.

|

| Ben Domenech: | But he also has defects.

|

| Pat Buchanan: | Oh of course he does.

|

| Ben Domenech: | Clearly morally, clearly other defects related to the kinds of people he associates with.

|

| Pat Buchanan: | You know a friend of mine said, “You know Pat, this isn’t the America we want. It’s the American we’ve got.” You deal with what you have. And I was for Trump because I believed, and yet believe there may be a hope that some of these policies can really be implemented and can work, and that I will be proven wrong, and that the country will make a great revival. But, you know. But I’m not sure I really believe that.

|

| Ben Domenech: | It seems right now, in the context of foreign policy, given that you’ve talked about wars a couple of times, that there is this what David Ignacious has called an “Iron Triangle” of these kind of praetorian guard between Mattis and McMaster, Kelly, and Tillerson. These people who basically are there to perhaps prevent Trump from doing something lackadaisically or off the cuff.

|

| Pat Buchanan: | I think they’re able, patriotic … You mentioned the generals. Every one of them are able, patriotic people. They’ve really seen an enormous amount of life, and some of its worst parts in combat. And they’re very solid people to have there. My concern is how many of the folks were saying, as their magazine, we started An American Conservative said, for heavens sakes do not march up to Baghdad. You know, we get there. We will meet all of the next hill. We’ll meet all the people that came before, the Russians, the Brits, all these other imperialists. Don’t do it. And we did it. How many of them got up and said, “No. It’s a mistake.”

|

| Who was the fellow, he was the intelligence fellow I used to argue with, a general, who said it would be the worst diplomatic and military mistake we ever made, and he proved right. He died around I think 2005 or something. But this is a disaster. I mean look at us … And what do I fear now? I see President Trump going over there, talking about an Arab-Sunni NATO. You know we really want to give out more war guarantees? Did anybody read what happens to the Brits and these people. They give out these war guarantees?

|

|

| Ben Domenech: | But it seems to me that what you see in that administration is less perhaps a vindication of your particular ideological view of this and historical view of this, and more kind of the restraint that comes from a military mindset. That the natural tendency is one to carry a big stick, but not use it.

|

| Pat Buchanan: | Well, I think that’s … I hope that’s the truth with the generals. But a couple of these generals, I will say, fought … They really despise, understandably the Shia in Iraq and the Iranians. It’s my concern is the next war, and there’s a big focus on it, the Saudis would like it, the Israelis would like it, the Neocons would like it. They want the United States to engage, I think, to do to Iran what we did to Iraq without sending in an army. And I think that’s my fear, is that we will get into another war, which would consume the Trump presidency. And when in heavens name would you get out of there.

|

| Look I agree, this is like Vietnam in this sense. All of us knew, once we went in there, that when we’d go out this thing could really go down. And it’s gonna be a horror show if it does. And it was. And I think … And they’re talking about putting more troops in Afghanistan. I can understand why they do, but we’re not gonna win that war. And if we do pull out, as I think we’re gonna one day, it’s going to be unshirted hell for those people there.

|

|

| Ben Domenech: | |

| It seems to me in looking back, there’s this thread that runs through from even before your arrival on the scene. But from 1992 to 1996 to 2008 to 2012, where you have the over performance of people who espouse a particularly populist brand of politics in Mike Huckabee and Rick Santorum. Low-funded campaigns that over-performed where they were. There’s something else that all three of you have in common, which is that you put your faith at the center of your life and your writings and your speeches. That you really don’t give a speech, without at some point acknowledging the role that that has and the importance in it.

|

|

| It seems that the first person who came along who embraced a lot of the economic agenda or similarly defended medicare, defended social security, said things about reconsidering trade policies, that type of thing, but actually had the success was Trump, who is perhaps the most thoroughly secular Presidential candidate that we’ve seen in modern times. When you consider that, do you think that social conservatism and faith, belief, allowed you and others who maybe shared in some of your views to be painted as Bible-thumpers who could be dismissed because of their beliefs or depicted as bigots because of them, in a way that Trump could not?

|

|

| Pat Buchanan: | I think there’s … You know, I’m a Catholic. I’m not Bible-thumpers like the other fellows. But of course Santorum, there’s no doubt, I mean culturally and socially on issues we are very, very similar.

|

| Ben Domenech: | That he takes it seriously.

|

| Pat Buchanan: | Yeah, he takes it seriously, and we elevate those issues. The question is social conservatism, it was a majority in America, but there’s a real question when you talk about the millenials and others, that if you elevate it, you’re going to antagonize those folks. Take same-sex marriage for example. Nobody was in favor of that … I mean I think the Clintonites were just outraged you know when I mentioned gay rights and things like that. That you’re misrepresenting our point of view. But that has moved so far, you talk to millenials and people I know, it’s not a concern with them.

|

| So I think, my feeling, is that you have to make a compromise with reality. And when I looked at Trump, and I said, look he’s not gonna … Matter of fact, I talked to him once about this, and you know he just, where should we come down on this one, you know? And my view is, look, the key is the Supreme Court. As long as he’ll appoint frankly, Supreme Court Justices, from the Federalist Society recommend, if they vetted them better than we did Carswell and Blackman.

|

|

| Then if you’ve got him, and he’s committed to that, you’ve gotta … To win now, or to hold power, we gotta have a coalition. That’s why I’m against some of my really right-wing friends, your anti … Paul Ryan. You know Paul Ryans a Kemp-ite, you know? And I’m not. But once you win with our populist border message, America First, you need to bring that together the way Nixon would’ve, and Nixon did. In order to hold these wonderful majorities you’ve got. They’re narrow in both houses, and if we get in a civil war with each other, the whole thing’s going down. We’re both going down, you know?

|

|

| What does the guy say? I remember they has some phrase back in the old days, said, “Look buddy if our end of the dinghy sinks, yours is not going to stay afloat.”

|

|

| Ben Domenech: | You know I guess the thought I basically have is this. There’s a thought in the media today, and certainly in the profiles that have been written about you recently, that Trump is a vindication of Buchananism. But it seems to me that that leaves out the faith and virtue side of what has always been a message of that.

|

| Pat Buchanan: | I think that’s correct. I think that’s correct. I mean there’s no doubt about the … I mean I have a big piece of stained glass given to me by one of my campaign staffers in ’92. It’s beautiful, and it says on it, “America First, Buchanan ’92” you know. So he took those themes. That represents … That’s really important when Trump does this, because that tells you what is behind. There’s a unifying sort of philosophy or idea behind economic patriotism, economic nationalism, securing the borders, belonging to one nation, one people. All of this thing to be part of the West. And I think Trump feels that, as opposed to really Macron say in France.

|

| Ben Domenech: | You know there’s been obviously enormous change in the Republican Coalition over the years, but it has to on some level, feel gratifying to you to see these ideas getting such attention at a time when we are 17-18 years removed from National Review effectively writing you out of the conservative movement.

|

| Pat Buchanan: | Right. I’ve been excommunicated several times by National Review.

|

| Ben Domenech: | But it seems to me that part of the problem-

|

| Pat Buchanan: | You know they didn’t … Actually in ’92, they endorsed me in New Hampshire. I think it was pretty funny, John O’Sullivan said … You know when I’m battling Dole, when I beat Phil Gramm in Louisiana, which was fatal. Because he said nobody else would go down to the state, and he said I’m going to get all 21 delegates. I got the caucuses locked up. So everybody said they wouldn’t go in there because Iowa told them don’t go in there, or it’ll hurt you in Iowa. So I waited til everybody stayed out, and I said, you know it’s a lot of Catholics down there. And so we went down there and worked it. And he never went in there, and we beat him.

|

| But you know, the point is, the fundamental part … What was the question again, because we came up to Iowa, and we were very, very strong. What was your question again?

|

|

| Ben Domenech: | My question was just how it feels to have your views vindicated kind of as something that is essentially part of the conservative movement 18 years after being written out.

|

| Pat Buchanan: | At that point, I don’t think that I was really written out of the conservative movement in ’92.

|

| Ben Domenech: | No, but in ’99.

|

| Pat Buchanan: | Well I ran Reform party.

|

| Ben Domenech: | Yes.

|

| Pat Buchanan: | I ran reform party. But what I was going to tell you. John O’Sullivan. This was the story. John O’Sullivan, the editor of The National Review, I said, you know and we got to New Hampshire, and he endorsed Phil Gramm in New Hampshire. I said, “John why did you endorse Phil Gramm? He was dead. It was down to me or Dole.” He said, “I know, that’s why we did it.” Because he couldn’t get away with endorsing me.

|

| Ben Domenech: | So it seems to me though that on reflection when you look back at that, one of the things that … It’s even I believe in the subtitle of the piece, is that what you represent is less conservatism than white-identity politics. And I think that the reflection that people would say when they look at Trump is similar to that, and similar frankly, to Nixon, where they would say, this is about white-identity politics more than it is about ideas or conservatism or free markets or free-

|

| Pat Buchanan: | Well, there’s nationalism but it’s not white nationalism. It’s American nationalism. It’s my belief anyhow. It’s us. We are one country, and one people. But as I’ve told you, we grew up in D.C. and half the population in D.C. is African American. And you know, African Americans when they visit Africa, they’re Americans. And it’s not simply because we’ve all read Jefferson, and we’ve all read The Gettysburg Address and the rest of the Neocon dogma you know.

|

| There is something about Americans that is unique and different, and people all over the world recognize and know that. So yeah, it is us. It’s not anti-them but it is us. And we have our own country, and our own history and heroes. You can talk about them, and holidays, and all of the things that make you an American, besides the fact that we’re quote … We have a democracy, so to speak. So I think those do, but I mean are the accusations … I think white nationalism is obviously a freighted term, but it’s much more modern. And it deals more with the alt-right I think, who are very open about it.

|

|

| Ben Domenech: | Well I don’t think that, I mean I think there’s a distinction that needs to be made there. There’s a difference between white nationalism and white-identity politics. Identity politics is neither bad nor good. It’s not necessarily saying that the chicken farmer in Indiana doesn’t have someone who’s going to look out for you. But what it does represent is basically making peace with a lot of different things about government that conservatives have typically criticized. Particularly programs that are targeted helping particular populations.

|

| Pat Buchanan: | Now let me say that, you know, the Catholics, you can go back, and we were steeped pretty much in Rerum Novarum in 1892, subsidiarity. And there’s a part of me that’s, you know I’ve got in arguments and fights with the unions because they wanted to dun me for some strike in New York, you know, in St. Louis. But there’s a part of me that is sympathetic to unions. The idea of unions. They were the best guys out there at the Globe Democrat.

|

| The union had gotten too strong, and too many demands. It was really not in its best period. But there’s a communitarian aspect there that I think that I have. Take social security now … I tell you what it is, Goldwater was going to make social security voluntary, gonna sell the TVA. The TVA didn’t bother me. And when you saw what they did, cutting that social security card in half, I was glad Trump said, “I’m not gonna fool with it.” You take our core constituency, Trump’s core constituency, if it is white folks over 65, I mean medicare and social security are pretty important to that crowd. And if you’re going to have a coalition, then that’s it.

|

|

| Look, we’ve lost those fights. I’ll tell you what, now I’m not … And I have sometimes … I’m not a libertarian. And I have real problems at times with that because it’s much more ultra-individualistic.

|

|

| Ben Domenech: | Sure.

|

| Pat Buchanan: | I mean you got Trump. I read Ayn Rand, John Gault’s 50-page speech. Now if that’s … It’s libertarian up at Hillsdale.

|

| Ben Domenech: | Yeah. There is a good bit. But here’s the thing that I feel like you’re saying there. You’re saying we’ve lost those fights. We can’t touch those things. At the same time, how does that live in a coalition with Paul Ryan, a Kemp-ite as you describe, who, while he doesn’t want to go the full libertarian of getting rid of these things, he does want to adjust them significantly.

|

| Pat Buchanan: | I understand that.

|

| Ben Domenech: | He wants to say, people are living longer. We can’t afford to be paying-

|

| Pat Buchanan: | You know I talked … I think it’s the Washington Post fellow. I think it’s Paul Samuelson but don’t quote. I was on it with … What was it? Morning Joe? I think it was, yeah. But I was sitting beside him, and he’s a liberal economist writing for the post. A very nice fellow. And he looked at me, and he said, “Pat, you and I could sit down in an afternoon and reform social security.”

|

| Ben Domenech: | Yes. It’s a math problem.

|

| Pat Buchanan: | We could do it. We could do it. And we all know, we know the five factors you’re going to have to deal with. So I agreed with him, and I would accept that. And I think that may have to be done. And I would agree, I almost agree to do it, but the question then becomes the politics of it. And I think Trump was smart, because we know what they will do to him if you come and just say …

|

| I mean that’s when I was with Nixon. When I used to, with Roger Ailes frankly, I did the telethons. I’d get all the questions, and I’d rewrite them and send them out to Nixon to answer on television. And he said, “Send me two questions every hour on social security.” This is ’68. And he wanted a solid for social security, I’m all behind it. You know? Because politically Goldwater had done that, it didn’t work. That’s established, and there are certain things that are, with due respect, they are there. I mean, 40% of our economy’s now spent by government. Okay it’s 57% in France, and we’re the conservatives.

|

|

| Ben Domenech: | Of course, one of the big motivations for immigration, one of the things that has pulled people in, are these programs. Particularly programs like medicaid that can really bring on a lot of people at the state level. And I’m curious about your thoughts on immigration in this context. It seems to me that most of the criticism that you have as it relates to immigration, is really a criticism of assimilation. That basically, you have communities that exist within the broader American community but not becoming of it. Thinking of themselves as Mexicans rather than Americans.

|

| Pat Buchanan: | Right.

|

| Ben Domenech: | And also having the luxuries that come with living in America, without actually having to deal with the challenges of living in a place like Mexico currently. What do you think though about the fact that we see, particularly among Protestant Hispanics, a series of rising incomes, of higher levels of assimilation. In a state like Texas, two-thirds of Hispanic Protestants voted for Ted Cruz. Do you think that this is something that is a problem that has to do with culture, or is it something that government enables?

|

| Pat Buchanan: | I think you’ve got a good point. Huntington spoke of the Hispanic thing. My problem with the Hispanic thing is the size of the cohort that’s in the country. It was about two-million I think, about 1950. It’s probably 60 million now headed for 100 million. And the whole idea, the elites, the country’s academic intellectual elites. They have given up on assimilation. As a matter of fact, they are inviting folks, when they come in here to maintain their traditions and their cultures. And this whole idea that you can have one country of many cultures, I just don’t … To me it becomes then, it becomes something of an empire. And it becomes like the Hapsburg Empire. And look all over, these places are coming apart.

|

| People want to be with their own kind. Now we had the Jewish ghettos and the Italian ghettos and all these great movies about New York, you know. Even The Godfather, they’re all down there in the Italian Ghetto. What happened was, and I’m part of that, you know, I’m second generation. But we peeled off and gradually became sort of the Catholic community. And you got into, what’s his name’s Protestant, Catholic, Jew in the country. You know.

|

|

| But now it is so many different folks from different cultures and countries and civilizations. And the melting pot is rejected, and the melting pot is not working. And the assimilation is not being done. And you know, I just don’t see-

|

|

| Ben Domenech: | But do you blame them, or do you blame the policies?

|

| Pat Buchanan: | I blame the elites. I blame the elites for not doing what they did to create Americans who are new people. Again, and I get back to … People will tell me-

|

| Ben Domenech: | Historically speaking.

|

| Pat Buchanan: | Yeah, and people tell me, you know The Federalist Papers and The Constitution, The Federalist Papers, The Declaration of Independence. The front of it, not the part where he’s dealing with the Indians, the front of it you know? And this is the things that make us Americans. Look, I never read those or studied those, I bet in high school or college or grammar school. We didn’t study those things. But we were Americans.

|

| Ben Domenech: | Somehow it seems, I think, people might get the order wrong when it comes to things like that.

|

| Tell us about the first time that you met Ronald Reagan.

|

|

| Pat Buchanan: | Well it was 1976, and I had come out of Gerald Ford’s White House. And when Ford appointed John Paul Stevens to the Supreme Court 96 to zip or something, I just told Sears, John Sears was a buddy of mine, that I’m with The Gipper. I’m with Ronald Reagan for the ’76 nomination. I was a journalist, and I was out there with Nixon at San Clemente, and I was invited up to have lunch with Reagan and Sears and Mrs. Reagan, and I think Mike Deaver. I think Lyn Nofziger.

|