Reading G.K. Chesterton’s work is a bit like a personal encounter with the Ghost of Christmas Present, from Charles Dickens’s “A Christmas Carol.” He’s a larger-than-life figure, with a writing style that’s both jovial and cutting. He paints a picture of reality you want to embrace, and he depicts what’s wrong with our world in a way that spurs the reader to action.

Thus today it seems fitting, especially considering the ideological rancor and spiritual disenchantment of our nation, to consider some of the best components of Chesterton’s work—and to encourage contemporary readers to “know him better, man.”

1. Chesterton Was a Bombastic, Prolific Genius

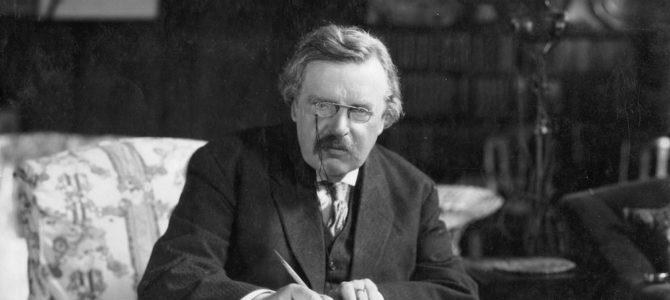

Gilbert Keith Chesterton grew up in London, and was baptized into the Church of England, although he described himself as an agnostic throughout his teen years. He embraced Anglicanism after his marriage, then converted to Catholicism in 1922.

Chesterton’s literary career began while working for publishing houses in London. He became a journalist, an art and literary critic, and the Daily News gave him a weekly opinion column in 1902. He went on to produce regular radio broadcasts, as well.

Among his early works, Chesterton’s “Father Brown” mysteries are undoubtedly his most successful and well known. In them, a bumbling yet thoughtful priest uncovers crime via his deep understanding of human nature. Another of his famous novels, “The Man Who Was Thursday,” turns our pompous ideologies on their head, promising a truth too powerful, mysterious, and even jovial for us to imagine.

Chesterton was 6’4” and weighed nearly 300 pounds. He wore a crumpled hat and a cape, often walking about with a cigar in his mouth. He was an astoundingly prolific writer—crafting thousands of essays, hundreds of poems and short stories, and 80 books throughout his lifetime. There’s perhaps no better introduction to his work than this, from James Parker writing for The Atlantic in 2015:

In his vastness and mobility, Chesterton continues to elude definition: He was a Catholic convert and an oracular man of letters, a pneumatic cultural presence, an aphorist with the production rate of a pulp novelist. Poetry, criticism, fiction, biography, columns, public debate—the phenomenon known to early-20th-century newspaper readers as ‘GKC’ was half cornucopia, half content mill. If you’ve got a couple of days, read his impish, ageless, inside-out terrorist thriller The Man Who Was Thursday. If you’ve got an afternoon, read his masterpiece of Christian apologetics Orthodoxy: ontological basics retailed with a blissful, zooming frivolity, Thomas Aquinas meets Eddie Van Halen. If you’ve got half an hour, read ‘The Blue Cross,’ the first and most glitteringly perfect of his stories featuring the crime-busting village priest Father Brown. If you’ve got only 10 minutes, read his essay ‘A Much Repeated Repetition.’ (‘Of a mechanical thing we have a full knowledge. Of a living thing we have a divine ignorance.’)

Chesterton was a journalist; he was a metaphysician. He was a reactionary; he was a radical. He was a modernist, acutely alive to the rupture in consciousness that produced Eliot’s ‘The Hollow Men’; he was an anti-modernist (he hated Eliot’s ‘The Hollow Men’). He was a parochial Englishman and a post-Victorian gasbag; he was a mystic wedded to eternity. All of these cheerfully contradictory things are true, and none of them would matter in the slightest were it not for the final, resolving fact that he was a genius.

2. Chesterton’s Friendships Defied Stereotype and Prejudice

Chesterton shared a lifelong friendship with George Bernard Shaw, the renowned Irish playwright and critic whose theological bent was decidedly counter to Chesterton’s. Shaw opposed organized religion and promoted eugenics, admired Stalin and Lenin, and termed himself at times an atheist or a “mystic.” Yet Shaw called Chesterton a man of “colossal genius,” and the two enjoyed a strong camaraderie:

‘If I were as fat as you, I would hang myself,’ Shaw once told Chesterton.

‘If I were to hang myself, I would use you for the rope,’ Chesterton replied.

In the introduction to a biography he wrote about Shaw, Chesterton wrote, “Most people say that they agree with Bernard Shaw or that they do not understand him. I am the only person who understands him, and I do not agree with him.”

The two men declare to us, schismatic and prejudiced against the “other” as we often are, that there can be such a thing as “friendly enemies.” We can enjoy the company of those different from us, even of those doggedly opposed to us. To have such friendships, however, we need a hearty dose of Chestertonian mirth: the ability to laugh at and with others, and most of all, to laugh heartily at ourselves.

3. Chesterton Skewered Our Therapeutic Fallacies

Last month Jesse Singal wrote a fascinating essay on the birth of the self-esteem movement in America. “During this span [the 1980s and 1990s], just about everyone, from CEOs to welfare recipients, was told — often by psychologists with serious credentials — that improving their self-esteem could… unlock the gates to more happiness, better performance, and every kind of success imaginable,” Singal notes. He goes on:

It would be hard to overstate the long-term impact of these claims. The self-esteem craze changed how countless organizations were run, how an entire generation — millenials — was educated, and how that generation went on to perceive itself (quite favorably). As it turned out, the central claim underlying the trend, that there’s a causal relationship between self-esteem and various positive outcomes, was almost certainly inaccurate. But that didn’t matter: For millions of people, this was just too good and satisfying a story to check, and that’s part of the reason the national focus on self-esteem never fully abated. Many people still believe that fostering a sense of self-esteem is just about the most important thing one can do, mental health–wise.

But the self-esteem movement, although it may have catapulted into pop cultural acclaim during the 1980s and ’90s, didn’t begin there. When Chesterton wrote his classic book “Orthodoxy” in 1908, he wrote it primarily as a response to the claim that “believing in yourself” was key to success and happiness.

“I know of men who believe in themselves more than Napoleon or Caesar,” he writes in the first chapter. “I know where flames the fixed star of certainty and success. I can guide you to the thrones of the Super-men. The men who really believe in themselves are all in lunatic asylums.”

Chesterton argues that “Complete self-confidence is not merely a sin; complete self-confidence is a weakness.” One of my favorite quotes, from the book’s opening pages, is this—not just a response to self-confident lunacy, but one which addresses our everyday temptations to self-centeredness:

But how much happier you would be if you only knew that these people cared nothing about you! How much larger your life would be if your self could become smaller in it; if you could really look at other men with common curiosity and pleasure; if you could see them walking as they are in their sunny selfishness and their virile indifference! You would begin to be interested in them, because they were not interested in you. You would break out of this tiny and tawdry theatre in which your own little plot is always being played, and you would find yourself under a freer sky, in a street full of splendid strangers.

Living as we do in a society of snowflakes and psychiatrists, such a prescription for happiness seems strange indeed. But the moment I see myself not as the most perfect snowflake in the world, but as one among many flawed, complicated human beings, I’m set free from my “tiny and tawdry theatre.”

4. Chesterton Was ‘A Mystic Wedded to Eternity’

Chesterton, much like C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien, spoke overwhelmingly to our culture’s increasing disenchantment, its imaginatively sterile and dour perception of the world. Chesterton prescribed mystery and enchantment as an antidote to this state of things, suggesting that we needed something more than logic in order to transcend madness and insanity: “Mysticism keeps men sane,” he writes in “Orthodoxy.”

As long as you have mystery you have health; when you destroy mystery you create morbidity. The ordinary man has always been sane because the ordinary man has always been a mystic. He has permitted the twilight. He has always had one foot in earth and the other in fairyland. He has always left himself free to doubt his gods; but (unlike the gnostic of today) free also to believe in them.

The fairy tale awakens our minds to the enchanted, mysterious nature of the real world we live in. It opens us to the possibility that mere atoms and molecules might be full of divine glory.

These tales say that apples were golden only to refresh the forgotten moment when we found that they were green. They make rivers run with wine only to make us remember, for one wild moment, that they run with water. … We have all read in scientific books, and, indeed, in all romances, the story of the man who has forgotten his name. This man walks about the streets and can see and appreciate everything; only he cannot remember who he is. Well, every man is that man in the story. Every man has forgotten who he is. One may understand the cosmos, but never the ego; the self is more distant than any star. Thou shalt love the Lord thy God; but thou shalt not know thyself. We are all under the same mental calamity; we have all forgotten our names. We have all forgotten what we really are. All that we call common sense and rationality and practicality and positivism only means that for certain dead levels of our life we forget that we have forgotten. All that we call spirit and art and ecstasy only means that for one awful instant we remember what we forget.

Many of the best works of literature—George MacDonald’s “Phantastes,” Lewis’s “Out of the Silent Planet,” Tolkien’s “Lord of the Rings,” J.K. Rowling’s “Harry Potter,” and countless others—fill us with a desperate longing for a moment, time, or feeling we haven’t fully encountered or experienced, but one that we want desperately.

Lewis described this as “joy,” a heaven-longing in our souls. He spent his entire life chasing it before he found it in Christianity. From the Norse mythologies of his youth to the wanderings and wonder of Narnia, Lewis wanted to capture this joy and hold on to it. But he found that—at least in this world—it’s a fleeting feeling. Chesterton suggests to us that this “joy” is a wild acknowledgement of mystery and meaning that floods us, then leaves us. Fairy tales make these moments possible.

“Fairy tales founded in me two convictions,” he writes. “First, that this world is a wild and startling place, which might have been quite different, but which is quite delightful; second, that before this wildness and delight one may well be modest and submit to the queerest limitations of so queer a kindness.”

5. Chesterton’s Christianity Offers Sanity In a Mad World

Many picture Christianity as either two horrid things: the first, a sort of dour and austere asceticism, which eschews the joys and pleasures of this world and embraces instead a gray and joyless religion. The second is a hypocritical malevolence, in which we say all sorts of sympathetic things, but act in an authoritarian, graceless way (see “The Handmaid’s Tale”).

Chesterton crushes both of these conceptions of Christianity, and defies them as heresy. He makes obvious the joy and mirth in our God, in the way he works and in the world he created. But he also points out that true Christian virtues are consistent, grace-filled, and glorious.

As we have taken the circle as the symbol of reason and madness, we may very well take the cross as the symbol at once of mystery and health. Buddhism is centripetal, but Christianity is centrifugal: it breaks out. For the circle is perfect and infinite in its nature; but it is fixed for ever in its size; it can never be larger or smaller. But the cross, though it has at its heart a collision and a contradiction, can extend its four arms for ever without altering it shape. Because it has a paradox in its centre it can grow without changing. The circle returns upon itself and is bound. The cross opens its arms to the four winds; it is a signpost for free travellers.

Regardless of what you believe, I challenge you to read G.K. Chesterton this summer. Take to heart his thoughtful, incisive, jovial criticisms of our culture. Consider his critique of rationalism, and the way it strips our world of meaning and mystery.

As for me, tonight, I’m going to read a fairy tale.