Ben Rhodes, Barack Obama’s erstwhile national security advisor, thinks the United States is “in a stronger position” now than it was eight years ago when Obama first came into office. In a recent interview with Politico, Rhodes characterized Obama’s foreign policy in curious terms. He said, “A lot of what we did was to restore the United States at the center of the international order.”

By nearly every measure, Rhodes’ claim is demonstrably false. From the Asia Pacific to the Middle East to continental Europe, Obama has greatly diminished America’s ability to shape and influence world affairs. Indeed, one is hard-pressed to name another period in our history marked by a more precipitous decline in American leadership abroad than that which we’ve witnessed over the past eight years. Space doesn’t permit a complete chronicle of Obama’s foreign policy blunders, but a salient few will suffice.

In Syria, nearly a half-million people have now perished in a civil war whose denouement has left that shattered country firmly in the hands of President Bashar al-Assad. Beyond the suffering he inflicted on his own people, Assad’s victory has demonstrated to the rest of the Middle East that America is no longer willing to invest in the stability of the region, and is content instead to let Assad’s sponsors, Russia and Iran, pursue their interests there. For Tehran, now flush with cash from Obama’s Iran nuclear deal, those interests are nothing short of regional hegemony.

Russia’s motivations in Syria, by contrast, have little to do with the Middle East and much to do with Ukraine and Eastern Europe. Left to its own devices by the United States after Russia annexed Crimea in 2014, Ukraine is now using Soviet-era tank factories to modernize its military in anticipation of a renewed Russian offensive. The shadow of a revanchist Kremlin stretches to Poland, which added 50,000 volunteer troops to its military last year in the form of local defense militias equipped with Polish-made arms. Similar efforts are underway in the Baltic states.

Dwarfing all these events is China’s lunge in the South China Sea, where the Chinese military is constructing armed island redoubts. Beyond asserting control over one of the world’s busiest shipping corridors, the purpose of the buildup is to sideline the United States and force our allies in the Asia Pacific to seek an accommodation with Beijing. Some, like Philippines President Rodrigo Duterte, appear to be getting the message.

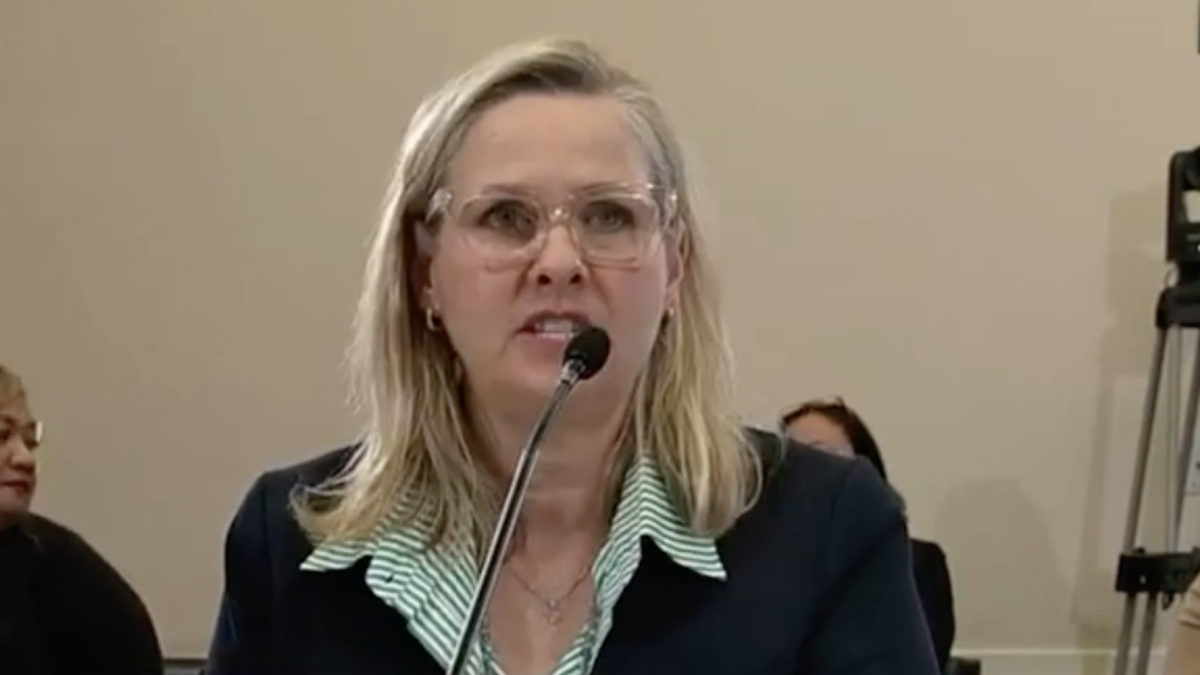

Rhodes Doesn’t Know What Diplomacy Is

In all this, Rhodes doesn’t see a systematic problem or a pattern of retreat. For him, the world is simply thus. He believes the “nature of power in the current moment” limits how much the United States can shape international affairs. From the end of the Cold War to 2002, he said, “the United States had a great deal of freedom of action… We could count on Russia being on its back foot as we enlarged NATO. We had some time before the Chinese started to try to shape events in their neighborhoods.”

Although Rhodes concedes that America is still the most powerful country in the world, “what has changed is there are other power centers that are going to ensure that there are limits on certain things that the United States wants to do.”

That’s the crux of Rhodes’ foreign policy thinking: he believes the rise of other powers is the cause of America’s constraint in world affairs, not a consequence of it. But in fact American inaction has emboldened other powers to pursue irredentist aims. This has been a cornerstone of Obama’s foreign policy thinking since the 2008 election, when he ran as an anti-war candidate. Obama promised to extricate us from President George W. Bush’s unpopular wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, and to reorient American relations across the globe. We would not impose our agenda abroad. We would not act unilaterally. We would not start any wars. We would, in effect, become just another nation in the family of nations.

Underneath Obama’s approach rests the assumption that American military action abroad is a destabilizing force. Hence, America’s true strength and influence flows from our restraint, from acquiescence to multilateral institutions and “international consensus.”

This represents a massive rupture in American foreign policy. Since the end of World War II, the United States had not been just another nation; it had been the indispensable nation. During the Cold War, American arms and aid underwrote global peace and prosperity in the West, and after the defeat of communism and the collapse of the Soviet Union, American leadership stabilized and sustained a rules-based international order that promoted free trade between nations, free elections within them, and the peaceful resolution of conflicts.

Obama set out to dismantle this Pax Americana, but he talked about it in the language of liberal internationalism. In his 2009 Cairo speech, Obama said that although the people of Iraq were better off without Saddam Hussein, “events in Iraq have reminded America of the need to use diplomacy and build international consensus to resolve our problems whenever possible.” In practice, that meant abdicating America’s leadership role. In the years to come, Obama would often invoke “diplomacy” and “international consensus” as reasons for refusing to intervene, even to maintain the post-Cold War international order.

Asked to sum up Obama’s foreign policy legacy, Rhodes echoed this line of thought. “We’ve engaged diplomatically around the world,” he said. “We’ve engaged former adversaries. We’ve engaged publics. We’ve sought to work through multilateral coalitions and institutions with the purpose of repositioning the United States to lead.”

But thinking of engagement in this way misapprehends the purpose of diplomacy and misunderstands America’s indispensable role. As former Secretary of State John Kerry has spent the last several years proving, diplomacy is pointless if it isn’t backed up by the credible use of force. In fact, the two go hand in hand.

Obama has often framed issues like the Iran nuclear deal as a binary choice between diplomacy and war. The truth is, the specter of war allows diplomatic engagement to be effective, because sometimes military conflict is the only thing that can provide leverage for negotiation. After all, diplomacy is first and foremost a negotiation. As Former Secretary of State Dean Acheson once said, “Negotiation in the classic diplomatic sense assumes parties more anxious to agree than to disagree.” For diplomacy to work, sometimes you need to make an adversary anxious to agree.

Syria Encapsulates Obama’s Foreign Policy Failures

No situation better demonstrates Obama’s failure to understand this than the Syrian civil war. By refusing to act after his “red line” ultimatum on the use of chemical weapons, Obama took military force off the table. At that point, there was no reason for Assad to negotiate a settlement. He knew he need only wait. Obama and Rhodes take credit for getting chemical weapons out of Syria under Russian supervision, but that’s a pyrrhic victory. Assad’s ultimate goal was to remain in power, not retain control of chemical weapons—many of which he never gave up anyway.

But Obama was determined not to let his presidency get mired in another Mideast war. In a widely-read piece on Obama’s foreign policy, The Atlantic’s Jeffery Goldberg rightly concluded that, “In the matter of the Syrian regime and its Iranian and Russian sponsors, Obama has bet, and seems prepared to continue betting, that the price of direct U.S. action would be higher than the price of inaction.”

The price of inaction, we now know, was civilian slaughter on a massive scale. But Rhodes and Obama talk about it with an air of fatalism. “You could call me a realist in believing we can’t relieve all the world’s misery,” Obama told Goldberg. “We cannot resolve the issues internal to these countries,” Rhodes said in his Politico interview. Rhodes also repeated a version of the rhetoric Obama often used when discussing the Iran nuclear deal, that it was a binary choice between the deal or war with Iran: “I don’t know how we could have started a military conflict with Assad that we didn’t feel compelled to try to finish by taking out Assad.”

Pretending American military action will inexorably lead to war and regime change is a way to justify the dismantling of the post-Cold War international order and America’s retreat from global leadership. But it’s also more than a justification: Obama and Rhodes really believe it’s true. The logic of their worldview demands that America not act, even when a leader like Assad attacks civilians with chemical weapons, or Russia invades Crimea, or China threatens its neighbors. Unless the U.N. Security Council is on board, America is powerless to act.

At his last speech to the U.N. General Assembly, in September, Obama said, “If we are honest, we know that no external power is going to be able to force different religious communities or ethnic communities to co-exist for long.” History and experience suggest otherwise, but for Rhodes and Obama, an America that’s unable to impose its will or uphold international norms is necessary for a better world—even if it means we have to sit back and watch it burn.