Earlier this year, the Library of Congress announced its annual selections for the National Recording Registry, a collection that celebrates and preserves audio recordings “recognized for their cultural, artistic and/or historical significance to American society and the nation’s aural legacy.” As always, it’s an eclectic list. The Columbia Quartette’s 1911 tune “Let Me Call You Sweetheart” and Metallica’s 1986 thrash metal album “Master of Puppets” sit alongside such non-musical selections as Secretary of State George Marshall’s 1947 Marshall Plan speech and radio coverage of Wilt Chamberlin’s 100-point game.

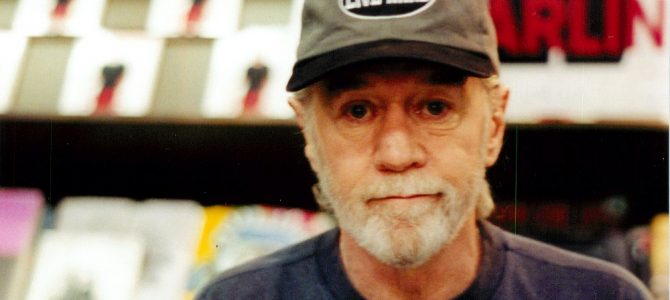

One item on the list is George Carlin’s 1972 comedy album, “Class Clown,” which features his classic routine, “Seven Words You Can Never Say on Television.” “Classic” seems an appropriate designation, because besides being a solid bit of standup, he devised the routine when the boundaries of acceptable language were being challenged on multiple fronts.

He was once arrested for performing it, and even the Supreme Court weighed in on whether the Federal Communications Commission could regulate such words on public airwaves. Carlin survived the controversy, of course, and went on to a long career as the nation’s comedic conscience and, later, its foul-mouthed elder crank, before he died in 2008. His observational humor, sardonic wit, and obsessive attention to language endeared him to thousands of fans, while earning him the enmity of critics who recoiled from his love of expletives.

The “seven words” routine clearly has a place in legal and comedy history. If you listen to it today, it’s still pretty funny. But if the Library of Congress really wanted to honor Carlin’s work, they might have picked another recording. While he became famous for addressing the censorship of words, he deserves our recognition for assailing the more insidious suppression of ideas.

On this front, his later work was far more probing, and much of it is as relevant as ever. Indeed, of all the hats Carlin wore in his life—juvenile troublemaker, zealous iconoclast, mischievous potty mouth, studious lexophile, inveterate atheist, and grumpy misanthrope—the one theme that runs through all of his best work is his staunch celebration of free expression from unfettered minds. In these strange times for free speech, that theme may also be the most important.

George Carlin Goes Off-Script

Given Carlin’s famed penchant for offending bourgeois sensibilities, it is easy to forget that he was an established (that’s to say “safe”) comedian for much of the 1960s. As a regular guest on evening talk shows and a stalwart of the nightclub circuit, he pulled down the then-princely annual sum of $250,000, and even flew to gigs in a private jet. Although his act occasionally hinted at his subversive side, he wore a tie and worked clean.

But Carlin was never satisfied with these trappings of success. Tired of blunting his sharper edges and telling saccharine jokes to middle-class men in suits, he revolutionized his act around the decade’s end. He embraced the counterculture, grew out his hair and beard, experimented with LSD, and thereafter took on the persona of cultural sage, bringing an unprecedented level of honesty to his observations on modern life. This new identity meant a significant pay cut at first, but it also freed him to showcase his verbal acumen. (His musings have garnered such respect over the years that dozens of bon mots have even been falsely attributed to him.)

He also began dabbling with off-color language, a point that deserves some context. He was far from the first comedian to work blue. Bawdy stage humor went back generations, and fly-by-night record labels and rebellious perverts had been trading illegal, “for adults only” party records since at least the 1930s.

But when Carlin was coming up at the turn of the 1960s, mainstream comedy from the likes of Bob Newhart and Nichols and May fit squarely into the vein of the family-friendly variety show. A few edgier comedians—Mort Sahl, Jonathan Winters, and Shelley Berman among them—produced material that was probing, satirical, antisocial, or borderline surreal, but these guys kept their language clean. So strong were the social restraints in Eisenhower-era America that Time dubbed these comics the “sicknicks” in 1959 simply because they dared deflate such sacred cows as “motherhood, childhood, adulthood, [and] sainthood.”

The chief crack in the picture window, of course, was Lenny Bruce, whose unabashed exploration of sex and profanity put him into a class by himself. His brand of iconoclasm was no mere academic exercise: you could actually be arrested for saying those things back then. Public expression laws varied by location, and cops and judges could be highly subjective. Bruce was arrested four times for—get this—saying words, and once even sentenced to four months for obscenity. (The young Carlin, too, was arrested at a 1962 Bruce performance for refusing a policeman’s order to show his ID.)

Bruce was hounded incessantly and eventually fell victim to his own demons, but he also played a part in stimulating the broader social transformations of the later sixties. While semi-legitimate comedy record labels began releasing raunchier material from the likes of Redd Foxx, baby boomers embraced the f-word as a countercultural, anti-authoritarian declaration. A few musical acts of the late sixties even slipped a surreptitious “f***” past the record label heavies. As a sign of this cultural shift, comedy recordings changed dramatically around 1970. Engelbert Humperdinck and the Carpenters now shared record store shelf space with Chitlin’ Circuit veterans Rudy Ray Moore and LaWanda Page and the countercultural stoners Cheech and Chong.

Profoundly influenced by these trends, Carlin and Richard Pryor took up the torch of honest, observational comedy, railing against an establishment whose humorlessness grew from equal parts mainline Protestant gentility and Main Street provincialism. The two men tread lightly at first, but in time each became his own successful brand of foul-mouthed enfant terrible for young comedy fans. “[Lenny Bruce] was the first one to make language an issue,” Carlin later recalled, “and he suffered for it. I was the first one to make language an issue and succeed from it.”

Pryor’s material was far more personal than Carlin’s, and his mastery of expletive gave his audience a window into the world that had shaped him. Whereas Bill Cosby had been highly successful in touting a brand of racial universalism in his many Grammy-winning comedy records of the late sixties, Pryor suggested there was something fundamentally different about the black experience in America.

This difference was not just experiential, it was also vernacular. As Bob Newhart later said of Pryor, “He was talking about the ghetto, and he needed to use the language of the ghetto. I’d feel cheated if Richard got up and said, ‘Gosh darn it.’” Carlin, by contrast, played the role of the troublemaking merry prankster who denounces authority and lampoons hypocrisy. He put profanity under a microscope as a biologist dissects an animal or an anthropologist studies the taboos of an isolated tribe.

Once Carlin had altered his standup aesthetic, he channeled his frustrations into the “seven words” bit, which first appeared on the 1972 live album “Class Clown.” At its core, this routine was about words—their subjective meanings, how they sound, and how people react to them. In questioning the prohibition of certain words, he hinted at a theme that would become more important to him in later years: the control of language as a marker of power.

But on a whole, the routine was a set of simple observations on the naughtier side of the mother tongue. “There are some people that are not into all the words. There are some that would have you not use certain words,” he told his audience. “There are 400,000 words in the English language and there are seven of them you can’t say on television. What a ratio that is. 399,993 to 7. They must really be bad. They have to be outrageous to be separated from a group that large! All of you over here, you seven: Baaaad Woooords.”

The routine has its moments, and the wild audience response to the actual seven words (you can look them up on your own) says a lot about the contemporary novelty of hearing them in a public setting. As Carlin put it, to raucous laughter, “Those are the heavy seven. Those are the ones that’ll infect your soul, curve your spine, and keep the country from winning the war!” Clearly there was something liberating about the comedian saying them and the audience hearing and applauding them, as though everyone in the theater were part of an elite brotherhood that was throwing a big middle finger at the establishment.

Yet in light of Carlin’s later reputation as a purveyor of the profane, this now comes across as a surprisingly tame performance. The “seven words” portion fills out only the final seven minutes of a 48-minute record of PG-rated topical bits on religion, medicine, and other mundanities. Moreover, “seven words” was hardly high art. Much of it was simple wordplay commingling with gratuitous profanity, as though he expected (correctly, it seems) the novelty of cursing in public to be enough to satisfy his audience.

The effect was a bit like the thrill a kid gets when he learns to swear around his friends, and thus exercises a degree of independence from his parents. By comparison, Carlin and his audience were declaring their independence from polite society and the cultural elite, but they weren’t doing much else. There’s an uncomplicated playfulness to the “seven words” bit on “Class Clown,” but the routine is about as deep as a birdbath.

“Class Clown” got some free publicity later that year when Carlin was arrested and charged with disorderly conduct for doing the routine at a public festival in Milwaukee. It was a fortuitous event, really: he enhanced his bona fides as a “dangerous” comic, but unlike his mentor Bruce, Carlin would never do jail time for his words. He was freed on bail, and a sympathetic judge threw out the case because the crowd had remained peaceful.

Times had certainly changed. As young people grew more cynical and traditional institutions saw their moral authority slipping, Americans began to tolerate more explicit entertainment as an acceptable byproduct of honest discourse.

From Seven Words to All Words

If Carlin’s career had ended there, he’d be little more than a footnote in comedy history. Fortunately, he reworked “seven words” into a razor-sharp performance that was as much about free expression as it was about naughty words. The routine’s basic premise—that words matter, and nobody can tell you what to say or think—undergirded his exploration of language and cultural values for the next 36 years.

For the rest of his life, his linguistic obsession was part inquisitive lexicography and part lighthearted wordplay, but it was just as often anti-authoritarian, aimed especially at the self-appointed language police who seemed to gain more influence with each passing year. In short, despite his flaws, Carlin rightly saw that efforts to control language are really efforts to control minds, and he targeted anyone who sought to impose these subjective rules on the rest of us.

This transformation didn’t happen overnight. A revised routine titled “Filthy Words,” which appeared on his follow-up record, “Occupation: Foole” (1973), did little more than expand the scope of the original seven. It was a funny bit, but hardly the stuff of a great comic innovator. (For what it’s worth, Carlin was also pretty coked up during this performance.)

This version of the routine is noteworthy for other reasons: When a New York station aired it, a listener complaint led the FCC to issue a reprimand. The Supreme Court later ruled that the routine was “indecent but not obscene” and that the FCC could regulate such material on the public airwaves. Before this time, in fact, the limits on broadcast language were rather vague, and the FCC actually took up Carlin’s dirty word list as its “unofficial, official” list of forbidden terms. “It’s a strange paradox,” notes the linguist Jack Lynch, “that a foulmouthed champion of free speech should have been instrumental in writing the law prohibiting those same words in the public airwaves.”

Perhaps the best version of “seven words” appears on his 1978 HBO special, “George Carlin Again!” By this time, the routine had become a more insightful take on the hidden power of the herd. He was still assailing the unaccountable, self-appointed moral arbiters and powerful media magnates who suppressed certain words, but at a deeper level he was indicting the social pressures that enforce self-censorship.

“What are these words that I’m talking about?” he asked rhetorically. “They’re just words that we’ve decided . . . not to use all the time. . . . And they’re the only words that seem to have that restriction. I mean, there are a lot of words you can say whenever you want, you know. . . . ‘Topography!’ No one has ever gone to jail for screaming ‘topography.’ But there are some words that you can go to jail for.”

He explained that he grew up learning about bad words by painful trial and error—that is, whenever he said one, his mother slapped him. So, he thought, there must be a list of the forbidden words somewhere. “I was just trying to find out which words they were, for sure,” he recalled. “All of them. I wanted a list. . . . Nobody even tells you, when you’re a kid, what the words are that you’re supposed to avoid. You have to say them to find out which ones they are.”

But in time he realized unwritten rules are often the strictest ones of all, and just as often the hardest to decipher. Even as a child, he began to suspect that adults were uncomfortable with complicated truths; they preferred instead the straightforward invocation, “Better not say that!”

As with the earlier versions of the routine, his staccato delivery of the actual seven words brought cathartic applause from the audience. This had become a ritual for his fans, and in a sense Carlin was still just dabbling with the true power of language. To be sure, taking on the concept of profanity was a way of challenging the unwritten social rules, and his modality was highly provocative.

But for Carlin, the more significant subtext was society’s troublesome alignment of personal character with one’s use of certain words. By what standard, he asked, are bad words the calling card of bad people? His experience suggested otherwise. The middle class had long sought to rein in the habits and speech patterns of working-class people, or at least to differentiate themselves from laborers through a set of carefully defined manners and clear linguistic boundaries. Never mind that profanity had been vital to socialization and solidarity-building for generations of working men.

“When I was a little boy in the ‘40s,” Carlin later recalled,

I was told to look up to and admire soldiers and sailors, policemen, firemen, and athletes, [who] were objects of childhood hero worship. We all know how they talk. So apparently these words do not corrupt morally. This was the thing I couldn’t put together. I use the words because I’m from that ethos. I’m from the street in New York, hung around in a tough neighborhood. It was common to curse, you make your point. It’s a very effective language.

Words as a Representation of Society

Carlin underwent another transformation in the late 1980s, one arguably more substantial than his earlier embrace of the counterculture. While he continued to thumb his nose at authority, he also began to espouse much harsher criticisms of American society.

This version of the comedian could be hard to take. Although his mind was sharp to the very end, some of his most astute observations were undercut by crude, agitprop condemnations of Middle America. Insightful and thought-provoking routines sat awkwardly alongside jags that were smug, misguided, misanthropic, or just plain cruel. Yet despite the occasional lapse, most of his jokes hit their target, and he never wavered in his commitment to free thought and expression.

This turn is evident on his 1990 standup album, “Parental Advisory: Explicit Lyrics.” Much of this material was consistent with his longstanding endorsement of plain-speaking (as when he asked why the perfectly descriptive term “shell shocked” had been replaced with the clinical mouthful, “post-traumatic stress disorder”), but clearly he was now operating on a deeper level.

He was especially irked by a development dubbed “political correctness,” which he perceived as just the latest method of obscuring uncomfortable truths. “I don’t like words that conceal reality,” he announced. “I don’t like euphemisms or euphemistic language. And American English is loaded with euphemisms, because Americans have a lot of trouble dealing with reality. Americans have trouble facing the truth, so they invent a kind of a soft language to protect themselves from it. And it gets worse with every generation. For some reason it just keeps getting worse.”

His chief target was the new language police. Unlike the earlier moral arbiters who had blushed at off-color humor and a few bad words, the new variety sought to control ideas. He briefly set his sights on the original culprits in thought control—government and his lifelong bête noire, religion—but there was little novelty in going after such low-hanging fruit.

What was new to the culture, and thus new to Carlin’s contrarian repertoire, was the troubling specter of a radically circumscribed political and social vocabulary. While religion and government were losing their legitimacy in some quarters, political interest groups were staking a powerful claim to the language. “Political activists, anti-bias groups, special interest groups, are going to suggest the correct political vocabulary,” he noted. “The way you ought to be saying things.”

Carlin had come of age when tolerating unpopular ideas was a central tenet of liberal thought, when urbane liberals championed open debate and free speech as a matter of principle—indeed, as a badge of their sophistication. But as the culture wars raged, Carlin grew to abhor the autocratic tendencies of his erstwhile allies. “Censorship from the right is to be expected,” he argued in 2002, “[but] censorship from the left took me by surprise. And I’m talking, of course, about what originated as campus speech codes at eastern universities and has come to be called politically correct language.”

As he recalled in the posthumously published “Last Words” (2009), the culture wars made it difficult for him to maintain his open, secular humanist inclination. “I was beginning to find a lot of my positions clashed,” he noted.

The habits of liberals, their automatic language, their knee-jerk responses to certain issues, deserved the epithets the right wing stuck them with. I’d see how true they often were. Here they were, banding together in packs, so that I could predict what they were going to say about some event or conflict and it wasn’t even out of their mouths yet. I was very uncomfortable with that. Liberal orthodoxy was as repugnant to me as conservative orthodoxy.

He elaborated on the problem of “soft language” in his 1997 best-seller “Brain Droppings.” As always, much of the material was as playful as it was philosophical, with lots of easy laughs at the expense of the linguistic technocrats. (“Kids aren’t ‘stupid’ or ‘dull’ or ‘lazy’ these days,” he complained, “they now have ‘learning disabilities’ or ‘Attention Deficit Disorder.’”)

But he took a sharp turn toward social commentary when he considered which words were offensive, and for what reasons. He had done much the same 25 years earlier in the “seven dirty words” routine, only with very different terms. This time he was railing against “the bastardization of our perfectly serviceable language” and “the PC Police” who had hatched the concept of “being offended.”

It seems as though you can barely open your mouth these days without “offending” somebody for some reason. I look at it this way – if I’m going to be offending somebody anyway, I might just as well speak precisely. At least there won’t be any question about what is making that person mad. Some people spend so much time and energy complaining about being offended that they never get around to solving whatever the original problem might have been.

By the time of his 2004 book, “When Will Jesus Bring the Pork Chops?,” he was highlighting the intellectual sleight-of-hand that had ushered in this new regime. “Political correctness is America’s newest form of intolerance,” he argued, “and it is especially pernicious because it comes disguised as tolerance. It presents itself as fairness, yet attempts to restrict and control people’s language with strict codes and rigid rules. I’m not sure that’s the way to fight discrimination. I’m not sure silencing people or forcing them to alter their speech is the best method for solving problems that go much deeper than speech.”

Carlin’s obsessions in this area went beyond his love of words. He believed that speech restrictions destroyed a comic’s sacred responsibility to the truth. Satirists and jesters have long been the last line of defense when the emperor is naked, and in our own time comedians are often the wisest sages in a world of evasions and doublespeak. As the writer Myron Tuman has argued, while we may sense falsehood in much of what passes for truth—“pieties that society seems content on making us accept”—and sense to be true much that is deemed false, we may be unable to counter the accepted position. “Caught in this dilemma, we turn to others—to storytellers and comics—to set matters straight, to speak the truth we cannot.”

George Orwell was even more succinct: “A thing is funny when . . . it upsets the established order. Every joke is a tiny revolution.” American comedians may or may not be suffering under oppressive conditions, but comedy is a dangerous game in many corners of the globe—even in Canada, as Mike Ward and Guy Earle will attest.

It is now clear in retrospect that Carlin was describing an emerging generation gap. With so many First Amendment battles already fought and won (including those waged by Carlin himself), younger people today seem less interested in defending free expression. There is data to suggest that, on average, millennials are willing to limit speech if it means protecting themselves and their peers from feeling offended. This is especially true on college campuses, where students are more likely than other adults to believe that freedom of speech is a well-secured right. Long gone are the quaint days, circa 1990, when students wore T-shirts declaring “Censorship Is Un-American.”

Of course, it’s unfair to characterize today’s students as infantilized totalitarians-in-training, as plenty oppose schools’ restrictions on political expression. Nevertheless, the social expectations on campus are so strict that many of today’s top comics won’t perform at colleges. Since Carlin was such a favorite on the college circuit in his heyday, one cannot help but wonder what he would think of today’s campus.

His free-thought advocacy was unabashedly liberal in 1972, but the traditionalist establishment he battled four decades ago has given way to a progressive one steadfastly dedicated to eradicating offense. The college revolutions of the sixties may have been fueled by free speech, but as Caitlin Flanagan has argued, “Once you’ve won a culture war, free speech is a nuisance, and ‘eliminating’ language becomes a necessity.” If Carlin were alive today, there’s no reason to believe he would put up with any of this nonsense. There’s even less reason to believe that any college would have him.

We’re Still Word Puritans

Much has changed since Carlin first performed “seven dirty words.” You still can’t say most of them on network television, but otherwise they’ve lost their sting. After a generation of Howard Stern, Jerry Springer, “South Park,” cable TV, gangsta rap, and the entire Internet, the f-word just isn’t what it used to be. “There’s no shock value left in words,” Carlin observed in his final interview. “Humor is based on surprise, and surprise is a milder way of saying shock. It’s surprise that makes the joke.”

It is a great irony of our age that while we’re now fearless on matters of sex and profanity, we’re still pretty uptight about words. New language rules have replaced the old, and new moral arbiters seem ever-ready to declare themselves the caretakers of our thoughts and speech. George Carlin rightly holds a place in the pantheon of America’s greatest comedians. He should also be a hero to all who cherish free thought, free speech, and the spirit of the First Amendment.