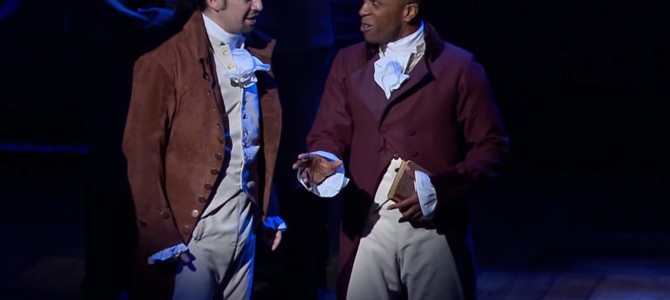

It can hardly be news to anyone that “Hamilton” is a terrific Broadway show, a tour de force that combines American’s cultural present with our historical past. It’s an intriguing, well-written, well-performed production that revives, as seems to happen about once a generation, our faith in musical theater as a vital art form.

Perhaps a large part of “Hamilton’s” success is because it is so unexpected. Some people don’t like hip-hop (like my husband, who adored it). Some wonder whether it would serve as a vehicle for the historical revisionism sweeping the academy (like me, and it isn’t). Is it a perfect show? No. I found the score so relentless as to be somewhat frantic in passages, and events may have seemed somewhat disjointed for those not already familiar with the story. But these are details besides the overall terrific performance which, as I said, is hardly news.

What was news to me is that “Hamilton” has something of an all-American, feel-good moment, and I was unprepared for the audience response when, about halfway through the second act, George Washington retired to Mount Vernon.

We Still Admire Restraint of Power

This episode was not on my list of big Hamilton moments. You think affairs, sisters, and above all duels. If you are being more serious, you think of the Revolution, the creation of our financial system, and (hopefully) “The Federalist Papers.”

Yet the moment when Washington voluntarily handed power to John Adams in March of 1797 is unprecedented in the history of democracy. Plenty of politicians in the various democracies that stretch from ancient Athens to the young United States had left office for various reasons—such as ill health, the end of a term, or, in most cases, losing an election. But never had a politician at the height of his popularity and powers with no legal impediment to seeking another term simply handed off the reins of government.

That was the moment in “Hamilton” when the audience really went wild—and it wasn’t just because it was a great song (which it was). We were cheering for Washington.

Perhaps it is because Lin-Manuel Miranda does such a good job of humanizing the Founding Fathers so they are neither super-human nor caricature (pace, Thomas Jefferson) that this passage gains such poignancy. By this point, the audience is painfully aware of how hard-fought the Revolution had been, how great the personal cost, and how challenging it was for all the principles—first and foremost Alexander Hamilton—to achieve greatness.

The internal conflicts and tensions inherent to democracy are already apparent under the first president, as is Washington’s enormous personal prestige and political skill, which enabled him to get outsized personalities such as Hamilton and Jefferson functioning together in his administration.

All of this must have made it all the more difficult for Washington to learn, as Manuel’s song says, to say farewell. When everyone with the possible exception of Martha, but very much including your beloved Hamilton, are begging you to stay; and when you can see the project you’ve spent your life on (establishing the United States) hangs in the balance; and when it is obvious to the meanest intelligence that you are the best person to nurture it along through the next crisis, you decide to step down.

Greatness Despite Imperfection

While some may say this was historically inconsequential since Washington would be dead two years later, the point is of course that Washington had no idea that would happen and he laid down all his political capital on demonstrating that the presidency of the United States was a short, not a lifetime, appointment.

In this year of all years, for an historian and close practitioner of democracy, this made the very steep price of attending “Hamilton” cheap. Without the efforts and sacrifices of very human individuals, we don’t have the United States. Without, for example, the tall, childless, wooden-teeth-wearing, slave-owning Virginian with a slightly odd personal life, none of it would have happened.

Theoretically we all know this, although I do credit “Hamilton” with my children’s familiarity with the Founders rather as I credit “1776” for my own. But the great gift of “Hamilton” is that it brings our heritage, as painfully imperfect as it may be, to the front of our collective consciousness. With that, it brings the realization that we have no reason to hang our heads. I have no idea who those people were who clapped and roared around me that Monday night, but in that moment we were all Americans.

While “Hamilton” is of course Alexander’s night, I don’t think he would mind his old boss stealing the show, just for one moment.