There are always plenty of reasons to complain about the Olympic games, if you are so inclined.

There is the usual debacle of the preparations for the venue, which is worse than usual this year, despite the fact that there is a simple solution. Or there is the unfolding live-action spy novel of the Russian doping scandal, to which the IOC has responded, to its credit, by banning a whole lot of Russian athletes.

Then there’s the television coverage, which if the past is any indication will go heavy on saccharine sob stories and overhype a couple of athletes who flop. Plus there’s Bob Costas, who I like, but who rubs some people the wrong way. Yet we have to have him there, because at this point, it’s just tradition.

So it’s easy, I suppose, to be cynical about the Olympics, and The Federalist‘s Rich Cromwell gives you his old-man-yelling-at-the-television version. But while the trappings of the games may be encrusted with a layer of corruption, as with any big institution, it’s worth remembering what the Olympics are really about at their core. They are a lonely and desperately needed outpost for a sense of striving, heroism, and human nobility. We need that this year more than ever, and we might even find in it the antidote for some of our cynicism.

The Ideals of the Olympics

The modern Olympics revive two crucial elements of the Greek ideal.

The first is the idea of a benevolent competition among rivals, fighting not to kill each other but to outdo each other’s achievements. The Olympic truce was the one time when the fractious Greek city-states would lay down their weapons, set aside whatever wars they were fighting amongst themselves, and compete like civilized people (more or less; there was always pankration).

It’s an example we can use right now when most of our political competition seems to be over which side is worse.

But the real core of the Greek idea was the pursuit of human excellence. This is expressed in Latin in the motto of the modern games: “Citius, Altius, Fortius”—”Swifter, Higher, Stronger.” The core story of the Olympics is about athletes who have spent years of dedication training to perform at the very highest level.

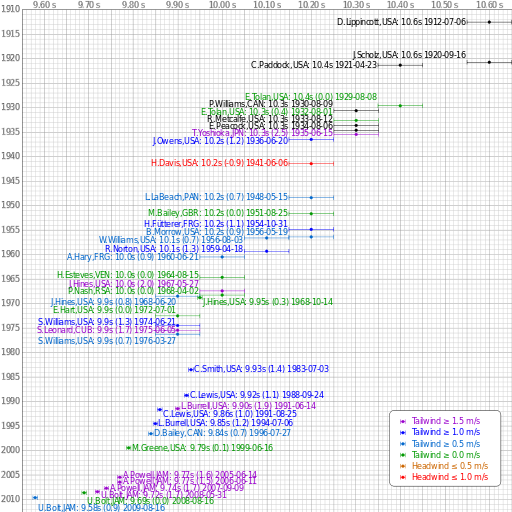

Yes, this might be a little hard to spot in table tennis—though it also strikes me as churlish to disparage other people’s enjoyment of niche sports. But the core of the games, and the most popular events, are the classics: running, swimming, gymnastics. As someone who has been watching the Olympics for more than 30 years, I’ve been amazed that the level of performance keeps getting higher and higher. Take a look at this chart of the progression of the signature event of the games, the men’s 100-meter dash.

Whenever you think the limits of human capability have been reached, someone pushes them just a little farther.

I wrote recently about the value of nudity in art, insofar as it represents an idealized view of human nature. This kind of idealization of the human form was central to Greek art and culture, and the closest we get to that in our own era—the closest we get to understanding how the Ancient Greeks saw mankind—is the Olympics. We rarely get it in the form of actual art these days, but we get it in the photos and television coverage of the lithe, toned, powerful bodies of athletes. It is a version of the human body that is idealized by virtue of being optimized for extraordinary athletic performance.

No, most of us are never going to be this fit, but that’s not what it’s really about. Our fascination with Olympic athletes comes from our ability to grasp a wider, abstract meaning. The extraordinary physiques of athletes are an easily grasped, visual symbol for the idea of extraordinary achievement as such. What we get from them is the idea of striving to make ourselves extraordinary in some way, even if it is not on the athletic field.

Plus There’s Sweet Music

That message is reinforced by another aspect of the coverage of the Olympic games that is somewhat unique in today’s culture: a soundtrack of heroic music, mostly thanks to John Williams, who has become even more of an Olympic institution than Bob Costas.

It’s music that makes you want to stand up straight, throw back your shoulders, flare your nostrils, and go run a marathon right now, this moment. Even if you have no earthly reason to think you could accomplish such a thing, Williams gives you a sense of what it would feel like if you could. Listen to this and ask yourself: what else in our music, or in our culture, gives you that sense of unlimited potential and uplifted purpose?

Speaking of Bob Costas, I want to say a word about why he has become an Olympic institution. He has the job of Mr. Olympics, for as long as he wants it, because of his remarkable preparation and depth of knowledge. Who else is going to be that interested in knowing the details about dozens of obscure sports and being able to pronounce the names of little-known athletes from around the world? And Costas is always fair-minded and objective in his coverage of the games. This is, alas, not the kind of dedication and mastery that we’re exactly used to seeing from journalists in other fields. But it’s what is required to measure up to the spirit of the games.

For all of our politician’s incoherent blustering about making America great again, Olympic athletes show us how to make being human great again. We might want to look at that with a little of the seriousness and even reverence it deserves. There are a lot of things that are wrong in the world, and a lot of that is going to smear off on the edges of the Olympics. But the games themselves are part of what’s right.

Follow Robert on Twitter.