“Steven Avery went to jail because his neighbors are racists.” So some would have us believe. This accusation is absurd (Avery is white, as are almost all of his neighbors), but it exemplifies the social prejudice uncovered by the Netflix docuseries “Making a Murderer.”

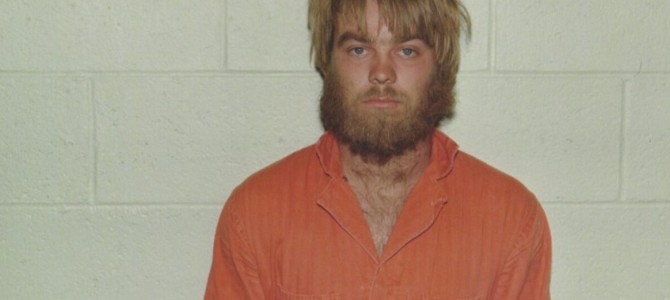

“Making a Murderer” tells the story of Steven Avery of Manitowoc County, Wisconsin. In 1985 Avery was wrongfully convicted of sexual assault, only to be exonerated in 2003 by improved DNA testing and through the help of the Wisconsin Innocence Project. Two years later Avery was behind bars, this time for the murder of Teresa Halbach, for which he was found guilty in 2007.

Through Avery’s story, the docuseries attempts to indict the American justice system. The producers thus portray Avery as the victim of an elaborate frame-up. A motive to frame Avery was easy to find. The series promotes the idea that the Manitowoc County sheriff’s department held a grudge against Avery for his exoneration in the 1985 case and because of his multi-million-dollar lawsuit against the county.

However, the producers had to find a motive for the civilians of Manitowoc County as well, as they would have had to be complicit in framing Avery as both witnesses and jurors. “Making a Murderer” portrays this motive as social prejudice, accusing his neighbors of looking down on Avery for being a poor junk peddler from the wrong kind of family.

“Making a Murderer” indeed uncovers social prejudice, not of Avery’s neighbors, but rather prejudice against rural communities and the white working class.

Those Racist Midwestern Rubes

Lorrie Moore, who up until a few years ago lived in Wisconsin, picks up on this theme in the New York Review of Books, and she runs with it:

The story one does see clearly here is really a story of small-town malice. The label ‘white trash,’ not only dehumanizing but classist and racist—the term presumes trash is not ordinarily white—is never heard in this documentary. Perhaps the phrase is too southern in its origins. But it is everywhere implied…. The entire family is socially accused: outsiders, troublemakers, feisty, and a little dim. What one hears amid the chorus of accusers is the malice of the village.

Frozen-hearted, malicious betrayal of one’s neighbors is in full view here, but it is not the hatred of small places but rather the naked selfish ambition of an author to cater favor with the name-makers of her craft by feeding the prejudices of their Ninth Avenue worldview.

Both Moore and the producers of “Making a Murderer” clearly perceive that within America there exists bias against the kind of people who were Avery’s neighbors, and that this prejudice is easily exploited towards their ends.

The bigotry they embraced, of course, is unfounded. The people of Manitowoc County are, as a rule, humble, gentle, and kind. Since the series is aimed at a general audience, it remains a little more modest in its prejudicial claims, but Moore’s piece, targeted as it is for the American elite, reflects a pervasive, hateful condescension among that subset towards people in huge swaths of America. This condescension is not only hateful, it is also irrational: “We all know those Midwestern rubes are racists, which is why Avery’s white neighbors turned against him, a white man.”

Coastal Elites Fiddle While Middle America Burns

I serve as a pastor of two churches in the region at the center of “Making a Murderer.” While hatred against the poor and lowly is not a problem here, the people do face all kinds of problems and challenges. The mortality rate in white, working-class communities like ours is rising. Heroin use is too common. Children are growing up in confusing and unhealthy domestic arrangements, surrounded by half-siblings and the children of their parents’ boyfriends and girlfriends.

This past fall I was astounded to see American elites losing their minds over Halloween costumes. While communities like mine face suicide clusters and drug addiction, Yalies wept over the possibility that someone might dress up like Pocahontas. It became clear to me that places like northeast Wisconsin could not look to elites in places like New York or DC for help with our problems; we would have to rely upon our own community and resources.

Reactions like Moore’s make me even more skeptical of the American elite. More than just being oblivious to real challenges, many elites, it would seem, actively hate people in places like Manitowoc County. Might such hatred work itself out in business practices and public policies that harm rural communities and working-class people?

There is hope for places like ours, though. The worldly authority wielded by America’s elites is only a mirage. Real authority rests with Someone Else. He loves all people, whether they work in a Ninth Avenue high-rise or a Lake Michigan shipyard, and because he loves them both he promises to reconcile them. But I think he might especially be sympathetic to people in places like Manitowoc County. He too worked with his hands. He too grew up in a small town.