“These bills mark the end of clean, open and transparent government,” declared Wisconsin Assembly Leader Minority Peter Barca (D-Kenosha). Evoking the customary hyperbole tethered to any effort to align campaign finance rules with the First Amendment, he added, “I fear for the future of democracy in Wisconsin.”

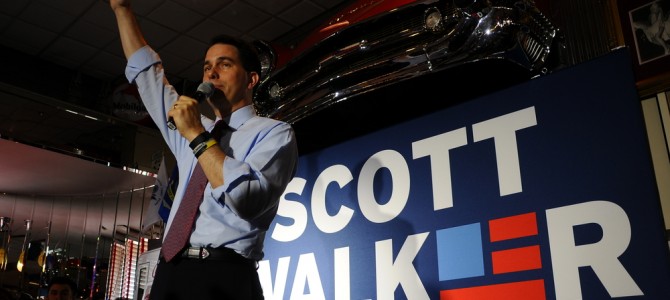

The bills Barca fears are three reforms catalyzed by the hopelessly corrupt and opaque “John Doe” investigations, which targeted Gov. Scott Walker and his allies. In five years, Milwaukee County District Attorney John Chisolm’s prosecutorial vendetta went from investigating the theft of some veterans’ funds to the attempted takedown of Wisconsin’s entire conservative apparatus.

In short, Wisconsin has transformed itself from one of the worst anti-speech campaign finance states to one of the best.

Now political John Does are no more, the Government Accountability Board (GAB) that oversaw Wisconsin’s elections has been disbanded, and the state’s campaign finance laws have been refined and restated in a more honest, First Amendment-friendly way. The Wisconsin story is a warning of what can happen when laws give prosecutors unfettered license to criminalize politics. But it also demonstrates the reform possible when victims fight back and legislatures recognize the constitutional rights of its citizens.

John Doe Gives Prosecutors Power to Silence Citizens

A “John Doe” is an investigatory tool similar to grand juries, which allows prosecutors to silence their targets ostensibly for their own “protection.” The reality is quite different. Some of Chisholm’s worst abuses are by now well-known: A man spends hours in jail, his orange-jumpsuit-adorned mugshot blasted across local television for no official reason. Pre-dawn paramilitary raids force an unclothed woman to run toward her door lest armed apparatchiks batter it down. A 16-year-old boy home alone told he can’t call his parents or school as government agents rummage through his house. Millions of documents seized, hard drives and cell phones confiscated, gag orders imposed; astronomical legal fees. And all based on a legal theory the Wisconsin Supreme Court declared in July completely invalid.

The fallout has been both legislative and legal. The legislature passed three bills completely reworking Wisconsin political regulations. The latter two—dismantling the GAB and reworking campaign finance laws—await the governor’s expected signature. On the legal side, John Doe’s victims have filed a flurry of lawsuits challenging the authority of government entities and asserting civil rights deprivations.

The old regime’s defenders warn of a coming “corruption” deluge and lament that now-legal “coordination”— combining strategy and pooling resources—creates troubling “loopholes.” Newly released documents from one ongoing lawsuit, however, reveals openness and transparency was not the order of the day on the prosecution side. Those running the show kept their intentions and motivations shielded from public view yet constantly tried to add additional government muscle to exert further pressure on their political prey.

Leftists Use Government Power to Silence Political Opponents

The questionable behavior began when Wisconsin Supreme Court’s most ardent leftist, former Chief Justice Shirley Abrahamson, appointed reserve Judge Barbara Kluka to oversee the second John Doe. Kluka approved the now-infamous warrants and subpoenas that eventually led to the investigation’s downfall. But shortly after the predawn raids began generating media interest, she recused herself, citing a previously undisclosed conflict.

A second judge then quashed the subpoenas and halted the investigation. Minutes from GAB meetings reveal a cozy relationship between Kluka, Chisolm, and the GAB. On June 20, 2013, the GAB judges and staff discussed Chisolm’s proposal that they join the John Doe and have a special prosecutor oversee the sprawling investigation. According to the minutes, “G.A.B. staff did not believe this would be an issue based on conversations with District Attorney Chisholm. [GAB] Judge Nichol was also confident based on conversations he had previously with Judge Kluka that she would be open to any requests from the GAB.”

In fact, Chisholm and the GAB practically dictated the investigation’s terms. On August 21, 2013, Chisolm’s office requested Kluka’s approval of GAB involvement, the appointment of a special prosecutor, who they wanted, and how much he should be paid. None of this was expressly authorized in the special prosecutor statute or in GAB’s enabling statute. But two days later, she approved all of it.

How Abrahamson, who wrote a lengthy dissent in the John Doe dismissal, came to appoint Kluka is also curious. The conversations Abrahamson had with Kluka, Chisolm, and the GAB judges is the subject of a public records request sent last July. She has not turned over any documents, yet they apparently exist and may provide information supposed defenders of “open” and “transparent” government don’t want the public to see. Abrahamson has hired a private attorney at taxpayer expense to represent her in dealing with the request.

‘Nonpartisan’ Attackers? Not so Much

Then there is Francis Schmitz—Chisholm and the GAB’s handpicked special prosecutor. John Doe defenders, including Schmitz himself, repeatedly cited his “Republican” credentials to bolster the investigation’s bipartisan veneer. But that doesn’t seem to be the case. According to meeting minutes, in his introduction to the GAB he acknowledged some minimal contacts with Republican officials when he applied for a government position, but stated “he had not made campaign contributions and was not currently active in any political party.”

There is also the GAB itself. Proponents lauded it as a national model because oversight by retired judges supposedly imbued it with disinterested nonpartisanship. But the people really running the show were partisan political operatives. Staff Attorney Shane Falk, the GAB’s most ardent John Doe advocate, was a former Democratic political appointee. Emails reveal not only his bias but the extent to which both the GAB and special prosecutor relied on his counsel.

After Kluka issued the subpoenas Schmitz began hearing from the targets’ attorneys. In one email, Falk complains that Schmitz—the person who is supposed to be in charge—is “really questioning the validity of the case.” In another, Falk muses Schmitz thinks he is “beating him up too much.” In another, Falk lashes out at Schmitz, accusing him of lying to the press about whether Walker was a target: “See the attached ‘target’ sheets from our search warrant and subpoena meeting. I see ‘SW’right up there near the top on Page 1. Is there someone else that has those initials?” He then adds curiously, “If you didn’t want this to have an effect on the election, better check [Walker’s Democratic opponent in the 2014 gubernatorial race Mary] Burke’s new ad.”

By February 2014 the second judge had quashed the subpoenas and Schmitz’s frustration with Falk boiled over in an email ending, “Wasn’t this your idea, Shane?” Falk wasn’t the only partisan in the supposedly nonpartisan GAB. After Walker signed Act 10 limiting public sector union rights, Nathan Judnic, another GAB staffer assigned to the case, tweeted the need for some “good old fashion rallying” and to “kill the bill.” Importantly, in November 2012, well before GAB’s official involvement, staff and Chisolm’s office started communicating about the John Doe not with their government emails but with Gmail accounts created specifically for that purpose. This of course made it easier to evade public records requests.

Please Prosecute Republicans So We Can Run the Show

The GAB’s lack of control over the investigation is further demonstrated by meeting minutes. In April 2014, after 10 months of official involvement, GAB Judge Harold Froehlich finally questioned whether it had authority to pay a special prosecutor or participate in the multi-county case in the first place. GAB Vice Chair Elsa Lamelas shared the concerns and sought that “in the future [we] not put ourselves in this position again.”

Incredibly, with the investigation halted and the entire façade crumbling, in May 2014 the staff recommended the GAB open a new civil investigation “without delay.” Two months later, the judges finally took control and voted the GAB out of the investigation completely. Perhaps coincidently, Falk left for private practice a month later.

Finally, there was coordination. The since-discredited theory of the second John Doe was that Walker’s strategizing with his allies enabled him to skirt campaign finance rules. Chisolm and the GAB did not see the problem, however, with doing the same thing in going after their targets. First Chisolm coordinated his investigation with four other district attorneys, then tried to bring in the state’s attorney general. After he was rebuffed, he went to the GAB and eventually got a special prosecutor appointed.

But that’s just the beginning. He also tried to get the U.S. attorney and the Internal Revenue Service involved. The feds declined because the case only involved state law, which would have been obvious to any first-year law student. But it didn’t stop there. GAB Director Kevin Kennedy—famously chummy with disgraced IRS official Lois Lerner—tried to get the Department of Justice involved 11 months later. Coordination, it seemed, was fine, as long it was on the Wisconsin taxpayer’s dime or involved the limitless manpower and resources of the federal government.

Common Sense Triumphs

Last July the Wisconsin Supreme Court finally ended the investigation, stating, “the special prosecutor’s legal theory is unsupported in either reason or law.” The legislature wisely determined it should never happen again. It passed three reforms that will change Wisconsin campaigns for the better and greatly reduce the power bureaucrats have over citizens’political activities.

The easiest reform ended political John Does. Henceforth, criminal investigations of political chicanery must go through grand juries, as in almost every other state and the federal government. Most importantly, this removes the routinely attached gag orders. Seventh Circuit Judge Frank Easterbrook described this feature as “screamingly unconstitutional.” Twenty-five years ago, the U.S. Supreme Court held that gag orders for federal grand jury witnesses were unconstitutional. John Doe supporters use terms like “efficient,” “compact,” and “less onerous” when comparing John Doe to grand juries. From the prosecutor’s standpoint, demanding a witness or target keep quiet or risk the slammer probably does aid efficiency. But there is the Bill of Rights.

Unfortunately the legislature didn’t end all John Does, but only enumerated where they may still apply, like felony-level narcotics investigations. But it reined in even those by limiting their duration to only six months, without an affirmative extension, and confining subjects to those originally investigated. Importantly, they also must account for the costs. Despite public records requests, Chisholm has never released a full financial accounting of the two John Does.

The second reform involved dismantling the GAB and replacing it with two separate boards: an ethics and elections board. Modeled after the Federal Election Commission, these boards comprise an even number of partisan appointees. The ethics board that will govern ethics laws for public officials, lobbying regulations, and campaign finance matters will include two former judges.

Critics complain the partisan feature means gridlock. These complaints mirror those at the federal level. FEC Commissioner Lee Goodman, however, disputes this, showing the FEC reached bipartisan agreement on 86 percent of substantive matters last year; not bad for hyper-partisan Washington. Moreover, when commissioners disagree, genuine disputes exist on the law and FEC authority. As noted above, it took 10 months for one judge to question whether the GAB had authority to be involved in the John Doe.

It is much more likely a bipartisan commission, even one including former judges, would not have moved forward on what was such obvious political targeting. Nor is it so easy under this scheme for partisan staff to capture investigations, as there will be watchdogs from both parties.

Finally, the legislature updated Wisconsin’s campaign finance laws to conform to court cases and a modern understanding of political financing. It doubled candidate contribution limits for statewide office from $10,000 to $20,000—limits that hadn’t been raised since the 1970s.

It also permits corporate and union contributions to political parties, and legislative campaign committees—the political organizations formed by the party caucuses in the Assembly and Senate, although not in the unlimited amounts as originally conceived by the Assembly. And it would only ban coordination on explicitly political advertising, allowing issue advocacy groups to work closely with candidates. The current bill also removes the requirement that contributors as low as $100 have their employers made public, which reduces potential harassment of low-level political participants.

Government Will Determine How Much Information You Need

The Senate missed a valuable opportunity by not allowing unlimited political donations to parties. Political scientists and scholars from all sides agree strong political parties are necessary for a healthy, functioning democracy. Reforms like McCain-Feingold gutted the parties, particularly at the state and local level, by eliminating intraparty communication and direct union and corporate contributions. Later, Supreme Court decisions like Citizens United—while an overall positive development for open, unfettered political discourse—further diminished the parties by placing them at a fundraising disadvantage.

Not everyone appreciates the new changes, however. Sen. Janet Bewley (D-Ashland) lamented, “What we’re doing is marching in lock step of money and money and more money . . . Instead of an informed decision, voters are going to be buffeted by a fire hose of information that will eventually limit their ability to cast a reasonable vote. Too much information is a bad thing.” Bewley implies, of course, that government should determine the magic formula that produces sufficiently “informed,” but not too informed, citizens that convey properly “reasonable” votes. The Constitution holds no such thing.

Complaints were not limited to Democrats. The sentiment was unfortunately shared by Rob Cowles, a Republican who voted against the reforms. His opposition originated from his mother, who “hated the garbage of politics . . . The mass mailings, the stupid TV ads, the fluff.” That “garbage” may be “stupid” for some, but the right to persuade, advocate, and pool political resources is at the core of the First Amendment. One state senator’s “garbage” is a Founding Father’s cherished constitutional right. One state senator’s “stupidity” was paid for in blood by irregulars and militia from Saratoga to Charleston.

The fallout from the John Doe debacle is far from over. Lawyers for one target, Eric O’Keefe, have asked a state circuit court to unseal documents in its GAB lawsuit. The GAB is vigorously fighting to keep those documents secret. No one except the lawyers knows what’s there. Other lawsuits and public records requests are also pending.

Regardless of what new embarrassing revelations are in pike, however, the damage is done and the witch hunts are over. Wisconsinites can now look forward to a more open political atmosphere.